FEATHER DAMAGING IN PARROTS

Feather Damaging (Plucking) in Parrots

by Rosemary Low

by Rosemary Low

The most serious behavioural problem encountered by companion parrot keepers is feather plucking and other feather damaging behaviours. It is no coincidence that this is frequently encountered with the most intelligent species: Greys, macaws and cockatoos.

Feather plucking is the removal or mutilation of feathers. It usually starts on the breast and/or thighs. Later the inner thighs and wings and, in Greys, the tail feathers might also be removed or bitten. This behaviour has similar characteristics to hair-pulling in humans (trichotillomania) and hair-pulling in mice, guinea pigs, rabbits, sheep, dogs and cats. It is

usually a psychological problem.

It should not be confused with feather loss in psittacine beak and feather disease (PBFD) which looks different and often includes the top of the head. Also, and especially in cockatoos, the beak becomes overgrown.

In Budgerigars, feather loss commences with the flight and tail feathers. This disease occurs in the wild. Feather plucking does not.

When does feather plucking occur?

It occurs after a stressful event, when a parrot spends too long on its own, when it is in pain, and due to hormonal changes when a bird becomes sexually mature or comes into breeding condition. It can also be seasonal -- not permanent. In many female parrots, especially Greys, plucking of the breast feathers occurs in May, with the warmer weather and lengthening hours of daylight.

What can you do?

Consult an avian vet. There are so many possible reasons. Disease can be detected. If the reason is psychological improving the circumstances under which the parrot lives is essential. Act quickly as soon as the problem starts. When it becomes a habit, it is usually impossible to cure. Eventually the behaviour may become ritualized and develop from a so-called maladaptive behaviour (trying to adapt to an inappropriate environment) to malfunctional behaviour (with abnormal brain function) – similar to addictions. This might,

in part explain, why many birds do not respond to treatment. It has been suggested that the actual cause is often “exposure to suboptimal environmental conditions in which the animal is faced with unresolvable conflicts” (Dodman et al,1997). “When the source of the conflict is removed, the behaviours may continue to be performed repetitively and pointlessly without a stimulus.”

Some vets suggest the use of a collar. It might help feather growth but it causes too much stress. Plucking is likely to resume when the collar is removed, until the cause is found.

Psychological reasons

1. Stress

The captive living environment of most parrots, especially single birds in the home, does not meet a parrot’s social and behavioural needs. This results in abnormal repetitive behaviours, including over-preening which leads to feather plucking.

Parrots are especially susceptible due to their high-level cognitive abilities (acquiring knowledge by reasoning and understanding what is going on around them). Also, they have been bred in captivity for a relatively short time. Very few species, and none of the larger parrots, can be considered domesticated. (Domesticated species are Budgerigar, Cockatiel, Peach-faced Lovebirds and a few other small parrots in which many colour mutations have been bred over several decades.)

Stress can include the introduction of another parrot to a household where a single parrot lived. In an aviary situation over-crowding or close proximity to aggressive birds can cause a parrot to pluck. However, note that some breeding females do pluck their breast feathers just before they lay. This is not unusual. In many species chicks are plucked in the nest.

They normally feather up quite quickly on fledging.

2. Hand-rearing.

Poor socialisation and absence of parents during the rearing period (resulting in failure to learn appropriate preening behaviours and routine) almost certainly makes a parrot more susceptible to feather plucking.

Because most hand-reared parrots are not socialised with their own species at an early age, they become over-dependent on human company. This makes them very anxious when left alone.

Too many breeders wean young parrots at an age that is much too early, thus when they go to a new home they are not feeding well and they are overwhelmed by a sense of anxiety. Most buyers of these birds fail to recognise that they are not properly weaned. Anxiety leads to feather plucking.

Reason 3. Poor nutrition.

Deficiencies of Vitamin A, calcium and fatty acids could lead to feather plucking.

Reason 4. Disease

A bacterial infection of the skin or feather follicles could cause plucking.

Examine the bird, including looking under the wings. A disease that causes pain could also be the cause. Immediate veterinary attention is essential.

Reason 5. A dry environment

Species from areas of high humidity, such as Greys and most Amazons and macaws, must not be kept near a radiator. They need baths or showers several times a week. Spray with a plant mister or provide a large dish for bathing. Water pots in cages are not adequate. If necessary, use a humidifier.

Reason 6. Smoking

Nicotine on hands is harmful to plumage. So is grease. Make sure your hands are clean when you handle a parrot. Contamination on the plumage could cause feather plucking.

Reason 7. Allergies and irritants

Do not use air fresheners in the same room, cleaning products or alcohol-based sprays.

Reason 8. Heavy metal poisoning.

Ingestion of zinc, lead and other metals causes heavy metal poisoning, often resulting in feather plucking. Zinc from welded mesh, especially poor quality mesh, keys, jewellery, fruit juice cartons lined with foil (offered as toys) and curtains with lead weights could be poisonous.

Some bird toys might also contain metal.

Feather plucking is the removal or mutilation of feathers. It usually starts on the breast and/or thighs. Later the inner thighs and wings and, in Greys, the tail feathers might also be removed or bitten. This behaviour has similar characteristics to hair-pulling in humans (trichotillomania) and hair-pulling in mice, guinea pigs, rabbits, sheep, dogs and cats. It is

usually a psychological problem.

It should not be confused with feather loss in psittacine beak and feather disease (PBFD) which looks different and often includes the top of the head. Also, and especially in cockatoos, the beak becomes overgrown.

In Budgerigars, feather loss commences with the flight and tail feathers. This disease occurs in the wild. Feather plucking does not.

When does feather plucking occur?

It occurs after a stressful event, when a parrot spends too long on its own, when it is in pain, and due to hormonal changes when a bird becomes sexually mature or comes into breeding condition. It can also be seasonal -- not permanent. In many female parrots, especially Greys, plucking of the breast feathers occurs in May, with the warmer weather and lengthening hours of daylight.

What can you do?

Consult an avian vet. There are so many possible reasons. Disease can be detected. If the reason is psychological improving the circumstances under which the parrot lives is essential. Act quickly as soon as the problem starts. When it becomes a habit, it is usually impossible to cure. Eventually the behaviour may become ritualized and develop from a so-called maladaptive behaviour (trying to adapt to an inappropriate environment) to malfunctional behaviour (with abnormal brain function) – similar to addictions. This might,

in part explain, why many birds do not respond to treatment. It has been suggested that the actual cause is often “exposure to suboptimal environmental conditions in which the animal is faced with unresolvable conflicts” (Dodman et al,1997). “When the source of the conflict is removed, the behaviours may continue to be performed repetitively and pointlessly without a stimulus.”

Some vets suggest the use of a collar. It might help feather growth but it causes too much stress. Plucking is likely to resume when the collar is removed, until the cause is found.

Psychological reasons

1. Stress

The captive living environment of most parrots, especially single birds in the home, does not meet a parrot’s social and behavioural needs. This results in abnormal repetitive behaviours, including over-preening which leads to feather plucking.

Parrots are especially susceptible due to their high-level cognitive abilities (acquiring knowledge by reasoning and understanding what is going on around them). Also, they have been bred in captivity for a relatively short time. Very few species, and none of the larger parrots, can be considered domesticated. (Domesticated species are Budgerigar, Cockatiel, Peach-faced Lovebirds and a few other small parrots in which many colour mutations have been bred over several decades.)

Stress can include the introduction of another parrot to a household where a single parrot lived. In an aviary situation over-crowding or close proximity to aggressive birds can cause a parrot to pluck. However, note that some breeding females do pluck their breast feathers just before they lay. This is not unusual. In many species chicks are plucked in the nest.

They normally feather up quite quickly on fledging.

2. Hand-rearing.

Poor socialisation and absence of parents during the rearing period (resulting in failure to learn appropriate preening behaviours and routine) almost certainly makes a parrot more susceptible to feather plucking.

Because most hand-reared parrots are not socialised with their own species at an early age, they become over-dependent on human company. This makes them very anxious when left alone.

Too many breeders wean young parrots at an age that is much too early, thus when they go to a new home they are not feeding well and they are overwhelmed by a sense of anxiety. Most buyers of these birds fail to recognise that they are not properly weaned. Anxiety leads to feather plucking.

Reason 3. Poor nutrition.

Deficiencies of Vitamin A, calcium and fatty acids could lead to feather plucking.

Reason 4. Disease

A bacterial infection of the skin or feather follicles could cause plucking.

Examine the bird, including looking under the wings. A disease that causes pain could also be the cause. Immediate veterinary attention is essential.

Reason 5. A dry environment

Species from areas of high humidity, such as Greys and most Amazons and macaws, must not be kept near a radiator. They need baths or showers several times a week. Spray with a plant mister or provide a large dish for bathing. Water pots in cages are not adequate. If necessary, use a humidifier.

Reason 6. Smoking

Nicotine on hands is harmful to plumage. So is grease. Make sure your hands are clean when you handle a parrot. Contamination on the plumage could cause feather plucking.

Reason 7. Allergies and irritants

Do not use air fresheners in the same room, cleaning products or alcohol-based sprays.

Reason 8. Heavy metal poisoning.

Ingestion of zinc, lead and other metals causes heavy metal poisoning, often resulting in feather plucking. Zinc from welded mesh, especially poor quality mesh, keys, jewellery, fruit juice cartons lined with foil (offered as toys) and curtains with lead weights could be poisonous.

Some bird toys might also contain metal.

Severe feather damaging behaviour

by a Grey Parrot

by a Grey Parrot

What do vets say?

Alan Jones: “Many owners appear to give their birds the best care but their parrot rips all its feathers out. Other parrots live in appalling environments but have immaculate plumage. What will solve the problem in one bird will have no effect in another.”

London-based veterinarian Chris Hall sees about 500 feather-damaging parrots every year: “Treatment is usually a combination of environmental enrichment, training, dietary change and the use of drugs -- usually mood modifiers, hormones or endorphin blockers.” ((Endorphins are released when injury occurs and can abolish the sensation of pain.)

Are drugs advisable?

These drugs can have undesirable side effects such as lethargy, depression, polyuria (too much urine), polydipsia (excessive thirst). If injected, the injection is stressful.

A trial using Fluoxetine was carried out on 24 feather-damaging parrots which had been examined and were disease-free. Most were captive-bred and hand-reared. Most started to pluck themselves aged between 10 and 13 months or shortly after abrupt changes within the household. They included six Greys and four Moluccan Cockatoos. The drug was no

successful. Side effects included frequent sneezing (two birds) temporary loss of co-ordination of muscles, also lethargy, one hour after medication given. There was memory loss in one Grey with a vocabulary of 250 words. (Source: Petra Mertens, Institute for Animal Hygiene, Munich.)

The best prevention and a possible cure:

Environmental enrichment and food enrichment

Parrot foraging toys and making a parrot work to find its food are extremely effective. Winny Weinbeck from the Netherlands told me about the dozens of foraging toys she has for her Grey, Galah and Amazon. Faced with a difficult puzzle in a foraging toy, the Grey would never give up until it had worked out how to get at the food, whereas the Galah and the Amazon lost interest if the task was hard. This underlines the importance of stimulating tasks for captive Grey Parrots in particular.

Environmental enrichment can be used to reduce abnormal behaviours and to improve the bird’s feeling of well-being. Experiments in contrafreeloading have been carried out with a number of captive animals. This means giving them the choice between free access to food

or making them “work” for it. I watched Winny fill the cardboard centre from a roll of kitchen paper with various small items of food, wrapped up in paper. When placed inside his cage, the Grey immediately explored this, removed the items and ate them. Winny said he always “forages” in preference to taking items out of the food bowl.

FDB research

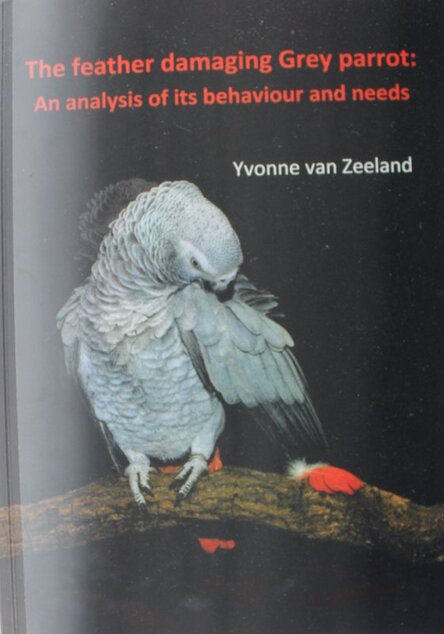

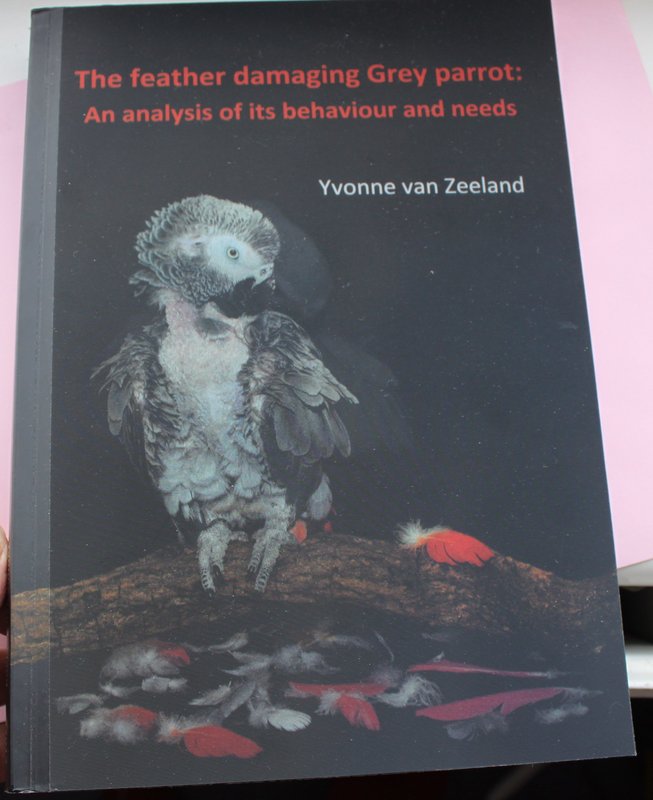

It is fortunate for parrot keepers worldwide that Yvonne van Zeeland decided to make this topic the subject of her PhD thesis, published under the title of The feather damaging Grey parrot: An analysis of its behaviour and needs. It has a totally unique cover, showing a Grey Parrot, partly denuded on the underparts, plucking or preening its shoulder. The floor below its perch is littered with plucked feathers. Tilt the book forward to another angle and the picture changes (presumably laser imagery) to a perfectly feathered Grey: the plucked feathers have gone.

Alan Jones: “Many owners appear to give their birds the best care but their parrot rips all its feathers out. Other parrots live in appalling environments but have immaculate plumage. What will solve the problem in one bird will have no effect in another.”

London-based veterinarian Chris Hall sees about 500 feather-damaging parrots every year: “Treatment is usually a combination of environmental enrichment, training, dietary change and the use of drugs -- usually mood modifiers, hormones or endorphin blockers.” ((Endorphins are released when injury occurs and can abolish the sensation of pain.)

Are drugs advisable?

These drugs can have undesirable side effects such as lethargy, depression, polyuria (too much urine), polydipsia (excessive thirst). If injected, the injection is stressful.

A trial using Fluoxetine was carried out on 24 feather-damaging parrots which had been examined and were disease-free. Most were captive-bred and hand-reared. Most started to pluck themselves aged between 10 and 13 months or shortly after abrupt changes within the household. They included six Greys and four Moluccan Cockatoos. The drug was no

successful. Side effects included frequent sneezing (two birds) temporary loss of co-ordination of muscles, also lethargy, one hour after medication given. There was memory loss in one Grey with a vocabulary of 250 words. (Source: Petra Mertens, Institute for Animal Hygiene, Munich.)

The best prevention and a possible cure:

Environmental enrichment and food enrichment

Parrot foraging toys and making a parrot work to find its food are extremely effective. Winny Weinbeck from the Netherlands told me about the dozens of foraging toys she has for her Grey, Galah and Amazon. Faced with a difficult puzzle in a foraging toy, the Grey would never give up until it had worked out how to get at the food, whereas the Galah and the Amazon lost interest if the task was hard. This underlines the importance of stimulating tasks for captive Grey Parrots in particular.

Environmental enrichment can be used to reduce abnormal behaviours and to improve the bird’s feeling of well-being. Experiments in contrafreeloading have been carried out with a number of captive animals. This means giving them the choice between free access to food

or making them “work” for it. I watched Winny fill the cardboard centre from a roll of kitchen paper with various small items of food, wrapped up in paper. When placed inside his cage, the Grey immediately explored this, removed the items and ate them. Winny said he always “forages” in preference to taking items out of the food bowl.

FDB research

It is fortunate for parrot keepers worldwide that Yvonne van Zeeland decided to make this topic the subject of her PhD thesis, published under the title of The feather damaging Grey parrot: An analysis of its behaviour and needs. It has a totally unique cover, showing a Grey Parrot, partly denuded on the underparts, plucking or preening its shoulder. The floor below its perch is littered with plucked feathers. Tilt the book forward to another angle and the picture changes (presumably laser imagery) to a perfectly feathered Grey: the plucked feathers have gone.

Yvonne van Zeeland is a veterinarian, a certified parrot behaviour consultant and a qualified European Specialist in Zoological Medicine (Avian). She explains that an estimated 10-15% of captive parrots either chew, pluck, bite or pull their feathers. She states: “Although the consequences of this self-inflicted feather damage may be solely aesthetic, medical issues may also arise due to alterations to the birds’ thermoregulatory abilities and metabolic demands, hemorrhage and/or secondary infections.”

Feather damaging might be interpreted as a way of coping with stress, loneliness or boredom in a barren environment. Poor socialisation and absence of parents during the rearing period (resulting in failure to learn appropriate preening behaviours and routine) might also play a part.

Eventually the behaviour may become ritualized and develop from a so-called maladaptive (trying to adapt to an inappropriate environment) to malfunctional behaviour (with abnormal brain function) – similar to addictions. This might, in part explain, why birds do not respond to treatment.

Part two of the thesis focuses on the value and efficacy of environmental enrichment for Grey Parrots. Various experiments are described that were carried out in a controlled setting. One was extremely interesting in revealing what captive Grey Parrots find most important in their lives.

The study was designed to determine how much effort parrots were willing to invest to gain access to specific types of enrichment, as an indication of their relative value to the parrot.

Six Grey Parrots were housed in a two-chamber set-up in which they were able to access specific resources by pushing a weighted door. The effort needed to gain access to the resource was gradually increased until a breakpoint was reached at which the parrot ceased to make successful attempts. Incidentally, the maximum pushing capacity of these six parrots was 732g (about 150% of body weight).

There were ten enrichment categories: destructible toys; non-destructible toys; foraging opportunity; auditory stimulation (a radio playing easy-listening music and three sound-producing toys); three cage mates; ladder, rope and net; a large room, 6.5m long; a large bath; hiding opportunity; empty cage.

In the publication there are results for three Greys. The most effort was expended to get into the large room. However, more time was spent moving around than flying. Yvonne van Zeeland told me that she thinks that this emphasises that parrots need to be let out of the cage and to be able to move around freely rather than being in a confined space. Living

trees, play stands and the opportunity to go outside would therefore appear to be beneficial.

The Greys in the experiment put a lot of effort into spending time with other Greys, more or less equalled by food availability. There was no interest in hiding opportunities and only one bird wanted to bathe.

As well as the above tests, eleven types of foraging enrichment were offered to the Greys, such as placing pellets in puzzle feeders, in order to determine how effective these were in increasing foraging time, which is an important behaviour to stimulate captive parrots.

The Greys were housed in cages 80cm long, 60cm wide and 155cm high.

Video recordings were used to analyse foraging times and activities. I will describe some of these devices to encourage parrot owners to provide similar opportunities.

• Four transparent plastic cups with lids dangling from a PVC pipe hung from roof of cage.

• Transparent acrylic wheel (diameter 15cm). Parrots needed to spin and turn the wheel to access food via a circular hole (2.5cm diameter).

Feather damaging might be interpreted as a way of coping with stress, loneliness or boredom in a barren environment. Poor socialisation and absence of parents during the rearing period (resulting in failure to learn appropriate preening behaviours and routine) might also play a part.

Eventually the behaviour may become ritualized and develop from a so-called maladaptive (trying to adapt to an inappropriate environment) to malfunctional behaviour (with abnormal brain function) – similar to addictions. This might, in part explain, why birds do not respond to treatment.

Part two of the thesis focuses on the value and efficacy of environmental enrichment for Grey Parrots. Various experiments are described that were carried out in a controlled setting. One was extremely interesting in revealing what captive Grey Parrots find most important in their lives.

The study was designed to determine how much effort parrots were willing to invest to gain access to specific types of enrichment, as an indication of their relative value to the parrot.

Six Grey Parrots were housed in a two-chamber set-up in which they were able to access specific resources by pushing a weighted door. The effort needed to gain access to the resource was gradually increased until a breakpoint was reached at which the parrot ceased to make successful attempts. Incidentally, the maximum pushing capacity of these six parrots was 732g (about 150% of body weight).

There were ten enrichment categories: destructible toys; non-destructible toys; foraging opportunity; auditory stimulation (a radio playing easy-listening music and three sound-producing toys); three cage mates; ladder, rope and net; a large room, 6.5m long; a large bath; hiding opportunity; empty cage.

In the publication there are results for three Greys. The most effort was expended to get into the large room. However, more time was spent moving around than flying. Yvonne van Zeeland told me that she thinks that this emphasises that parrots need to be let out of the cage and to be able to move around freely rather than being in a confined space. Living

trees, play stands and the opportunity to go outside would therefore appear to be beneficial.

The Greys in the experiment put a lot of effort into spending time with other Greys, more or less equalled by food availability. There was no interest in hiding opportunities and only one bird wanted to bathe.

As well as the above tests, eleven types of foraging enrichment were offered to the Greys, such as placing pellets in puzzle feeders, in order to determine how effective these were in increasing foraging time, which is an important behaviour to stimulate captive parrots.

The Greys were housed in cages 80cm long, 60cm wide and 155cm high.

Video recordings were used to analyse foraging times and activities. I will describe some of these devices to encourage parrot owners to provide similar opportunities.

• Four transparent plastic cups with lids dangling from a PVC pipe hung from roof of cage.

• Transparent acrylic wheel (diameter 15cm). Parrots needed to spin and turn the wheel to access food via a circular hole (2.5cm diameter).

Acrylic wheel: an excellent foraging toy.

• Honeycomb transparent acrylic feeder (8cm x 18cm) containing a cardboard box filled with food. The birds had to shred the box to reach the food. (The latter two are commercially available parrot foraging toys.)

One of the aims was to increase the time taken to extract the foods. In the wild, depending on the species and season, it takes parrots several hours daily to find and consume food. In a captive environment, these activities may take less than one hour and are too predictable and easy, unless the parrot must “forage” to obtain food. Foraging toys or puzzle feeders

appear to be the most effective measures to increase activity, stimulate, alleviate stress and boredom and reduce and prevent aggression. Foraging enrichment is quite a wide term, which also included using multiplebowls or mixing food with inedible items but they are less effective than the toys.

Yvonne van Zeeland and her researchers studied healthy (eleven) and feather-damaging (ten) Greys on the assumption that the latter would feed from bowls in preference to feeding from toys. This assumption was proved to be true. FDB parrots spent approximately 21% of the feeding time foraging while in healthy birds this was approximately 50%.

These examples are just a small part of the trials and conclusions described. They highlight the fact that to try to prevent the onset of FDB the key is environmental enrichment.

Reference cited:

Dodman, N.H., A. Moon-Fanelli, P.A. Mertens et al, 1997, Veterinary models of OCD in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorders (E.Hollander and D.Stein, eds), Marcel Dekkar, New York: 99-143.

One of the aims was to increase the time taken to extract the foods. In the wild, depending on the species and season, it takes parrots several hours daily to find and consume food. In a captive environment, these activities may take less than one hour and are too predictable and easy, unless the parrot must “forage” to obtain food. Foraging toys or puzzle feeders

appear to be the most effective measures to increase activity, stimulate, alleviate stress and boredom and reduce and prevent aggression. Foraging enrichment is quite a wide term, which also included using multiplebowls or mixing food with inedible items but they are less effective than the toys.

Yvonne van Zeeland and her researchers studied healthy (eleven) and feather-damaging (ten) Greys on the assumption that the latter would feed from bowls in preference to feeding from toys. This assumption was proved to be true. FDB parrots spent approximately 21% of the feeding time foraging while in healthy birds this was approximately 50%.

These examples are just a small part of the trials and conclusions described. They highlight the fact that to try to prevent the onset of FDB the key is environmental enrichment.

Reference cited:

Dodman, N.H., A. Moon-Fanelli, P.A. Mertens et al, 1997, Veterinary models of OCD in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorders (E.Hollander and D.Stein, eds), Marcel Dekkar, New York: 99-143.

All photographs and text on this website are the copyright of |