GO WEST FOR PARROTS

|

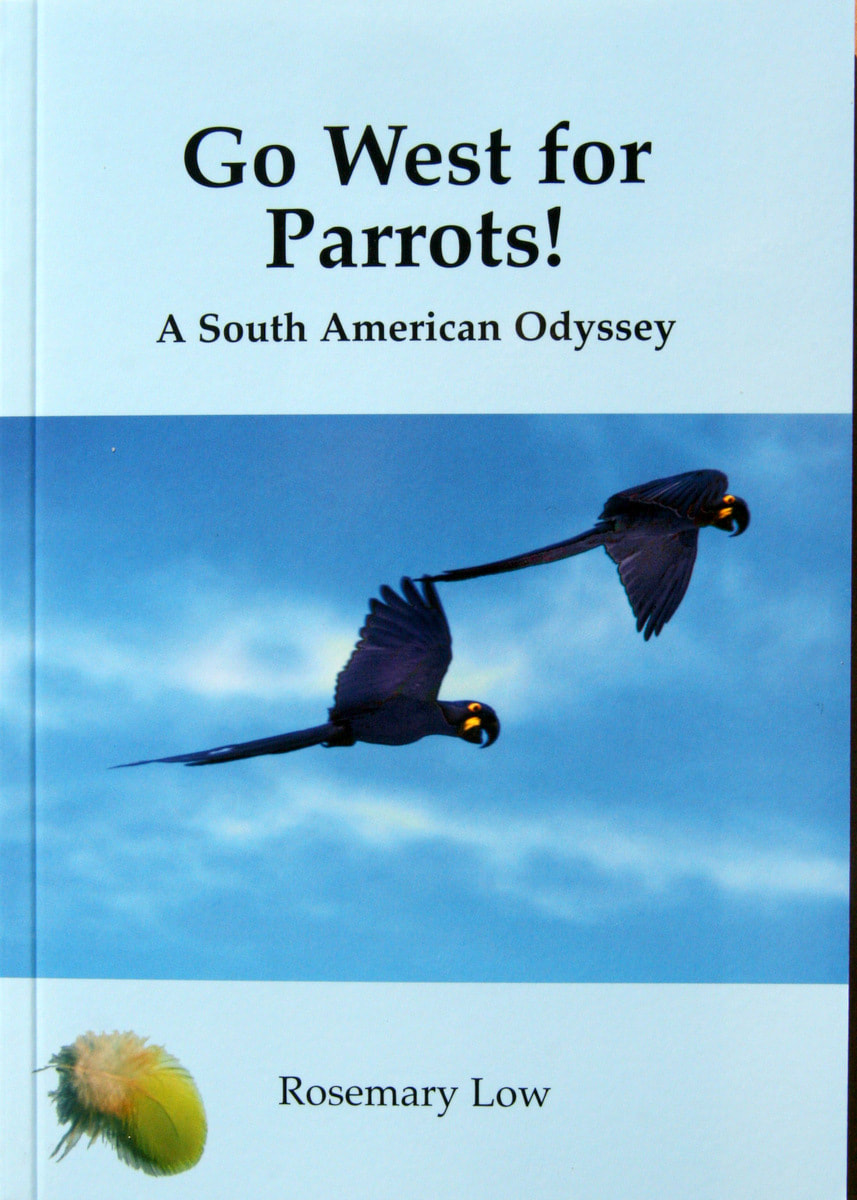

Go West for Parrots! An inspiring travel book for lovers of parrots and nature. 320 pages 100 mono illustrations 18 maps Paperback Book was £10.95 NOW ONLY £6.95 To purchase this book please click here or on the picture to go to the Bookshop |

SCROLL DOWN TO READ A SAMPLE CHAPTER FROM THIS BOOK

REVIEWS

REVIEWS

A big hit with reviewers!

Rosemary Low brings together her experiences of journeys to the Neotropics beginning with a trip to the Caribbean in 1975. Over the next 33 years her trips involved explorations in a large number of South American countries. The emphasis is firmly on the parrots but includes other birds, fauna, habitats, places, people, cultures and adventures… Knowing of her parrot passion, interest in geography and travelling, I thought it would be an absorbing book, and how right I was!

Rosemary kept detailed travel diaries on most of her trips, and this, along with being able to refer to her many published articles, gives accounts of even her earliest trips a satisfying immediacy… an interesting and informative book. Highly recommended for bird-lovers, especially parrot enthusiasts.

Graeme Hyde, Cage & Aviary Birds, March 4 2010.

This book will appeal to a wide audience, not only aviculturists and twitchers, but to those who enjoy tales of exploration and wish to know a little of the environment of the countries visited. Rosemary vividly sets the scene, recalling all sensory experiences so that the reader can imagine themselves with her. Her sheer enthusiasm for the jungle forests, flora and fauna is infectious and makes you want to read on further. She writes: “The lure of parrots in the wild draws me back to the tropics over and over again. It provides me with a satisfaction that is unlike any others and strengthens my desire to aid their conservation.”

Each chapter includes a map highlighting the areas mentioned, photographs of several of the birds described and an ecological update, the inauguration of a Conservation Area or recent figures relating to the increase/decrease of a particular species.

… This is a book I have particularly enjoyed reading and one I can wholeheartedly recommend to others who enjoy tales of birds, people and unknown localities. Buy now for an engrossing read.

Eunice Spilman, Amazona Society magazine, February 2010.

A definite must-read for parrot lovers, perspective travellers, and those arm chair travellers who would like to escape and travel vicariously through the author’s descriptive accounts of her South American birding adventures…. You can feel Rosemary’s excitement and fascination as she shares some of her most treasured moments of travel. As a parrot lover myself, this book truly fulfilled my craving/desire to read and learn more about parrots. However, this book opened my eyes to admire and value a wider variety of birds. For example, it’s hard not to share the author’s enthusiasm as she recounts the performance of a male Golden-collared Manakin displaying his courtship dance to gain the attention of a potential mate. Or the emotional impact the author felt observing the breathtaking beauty of eight to ten Cock of the Rocks dancing at a lek in Ecuador.

Rosemary was ahead of the times as far as eco tourism birding. A lot has changed in 30 years. She writes: “Today’s birders don’t know how lucky they are!”

This book describes the advances and accomplishments of conservation projects that have helped parrots live longer, better lives in the wild. From land purchases and creating Natural Park reserves to protect habitat and safeguard the parrots; to reintroductions of Scarlet Macaws in Costa Rica by Amigos de los Aves; the reintroduction of Blue and Gold Macaws by Bernadette Plair in Trinidad…

This book was enlightening and fun! Like I was reading my own diary notes of trips I have taken with my husband Mark. Many to the same locations, so I can honestly say this highly regarded author of more than 20 books conveyed an accurate description of the places and projects she visited.

Marie Stafford, Parrots International on-line magazine: 1, 2010.

For those of you who think that Rosemary Low only writes books about parrots -- think again. Although weighted towards parrots, Rosemary’s latest book -- Go West for Parrots! -- is a fascinating insight into Rosemary’s travels over the past 30 years and the vast array of species and people that she has encountered. It is as much a travel log as it is a bird book and as such will be equally treasured by the traveller as it will be by the naturalist.

With its stunning cover shot of Hyacinth Macaws flying over the Pantanal to its charming hand-drawn maps, this book is one which you will find difficult to put down. Rosemary has surpassed herself with the simple but highly effective layout of the book; each chapter covers a particular South American country or island group, and each country has an insert panel within the chapter, with details of interesting and sometimes little known facts about the area. Each chapter concludes with a list of species mentioned in the text, together with their scientific names. .. Each chapter is neatly rounded off with an update, providing details of the latest conservation measures being taken in the area, the current status of the birds, if it has changed, and, even in some cases, updates of the characters she met.

The book is illustrated with numerous photographs which really bring the book to life; these vary from images of the swamp men in Trinidad to Bolivian market scenes and the tranquillity of the Argentinian lakes; and, of course, a wealth of images of birds and other animals. If I had one criticism it would be that all the photographs are in black and white.

In typical Rosemary style, this book is packed with well-written descriptions of wildlife, habitat and the amazing and often humbling characters that she has encountered in her travels. Whether you read it from cover to cover or just dip in to find out more about your next holiday destination, you will not be disappointed. This book deserves a much wider audience than just the avicultural and natural history market. When you buy a copy, why not buy a second copy and give it to a friend who knows nothing about birds. I guarantee that they will enjoy it and, if it does not awake a dormant naturalist and conservationist in them, I will be truly surprised.

David Woolcock (Curator, Paradise Park, Cornwall), Avicultural Magazine.

Translated from the German by Tony Pittman

A spectacular volume with impressive photos of the wild does not await the reader, but a type of travel diary with all the highs and lows, which travellers in remote regions generally experience. The illustrations are monochrome and the maps are drawn by hand. In contrast to other travellers, who are only interested in parrots and parakeets and often wilfully ignore the country and its people, Rosemary Low is enthusiastic about hummingbirds, manakins, raptors and other rare birds and describes comprehensively the not always straight-forward working conditions of local conservationists and the life of the local people… She condemns the destructive greed of oil companies, which in Ecuador seek to destroy the ‘crown jewels’ of the Amazon, praises the successful activities of conservationists in Costa Rica and Argentina, and censures the habitat destruction rolling over Central America.

It is gripping to see how things have changed in the time she has been involved (the author describes 23 journeys taken between 1975 and 2008). This situation was decisive for the author to write this very readable book. Low wishes to alert the reader to the problems of neo-tropical parrots before it is too late.

Rainer Niemann, Papageien, April 2010.

Go West for Parrots ! Comments from readers

Carlos Keller, Brazil

I’m nearly finishing your book and it’s fantastic! I think it’s one of your best books. You’re really a good writer. I was very glad to read about your visit at my farm and I was wondering how are you able to memorize everything in a so detailed way. I never saw you taking notes, but without a journal made every day it would be impossible. Now I’m waiting for the next volume, something like: Go East for Parakeets!

Olivier Chassot, Costa Rica

We would also like to thank you very much for sending us your new book. It was great to be able to share your adventures since the mid seventies, and imagine all the wild places and amazing parrot species that you have had the chance to admire! It was also very exciting to read about some of our colleagues and friends, and of course, we enjoyed a lot your chapter on the Great Green Macaw in Costa Rica. I read the book for Christmas, almost without stopping and really liked it. This was a wonderful gift from you. Thank you again.

Bernadette Plair, Trinidad and USA.

What a delightful and informative narrative of your travels and experiences over the years with parrots and other species in the New World. You are truly an amazing writer.

I was totally surprised to see the chapters you wrote on Trinidad and Tobago. What an amazing tribute to the work done by the people there. Thank you for documenting your experiences with the locals and sharing the true spirit of community based conservation. I am humbled that you attributed so much to me because I could not have done any of it without their help and support. I feel honoured to be represented in your book and to be called a friend by someone with your vast knowledge and outstanding integrity.

Rosemary Low brings together her experiences of journeys to the Neotropics beginning with a trip to the Caribbean in 1975. Over the next 33 years her trips involved explorations in a large number of South American countries. The emphasis is firmly on the parrots but includes other birds, fauna, habitats, places, people, cultures and adventures… Knowing of her parrot passion, interest in geography and travelling, I thought it would be an absorbing book, and how right I was!

Rosemary kept detailed travel diaries on most of her trips, and this, along with being able to refer to her many published articles, gives accounts of even her earliest trips a satisfying immediacy… an interesting and informative book. Highly recommended for bird-lovers, especially parrot enthusiasts.

Graeme Hyde, Cage & Aviary Birds, March 4 2010.

This book will appeal to a wide audience, not only aviculturists and twitchers, but to those who enjoy tales of exploration and wish to know a little of the environment of the countries visited. Rosemary vividly sets the scene, recalling all sensory experiences so that the reader can imagine themselves with her. Her sheer enthusiasm for the jungle forests, flora and fauna is infectious and makes you want to read on further. She writes: “The lure of parrots in the wild draws me back to the tropics over and over again. It provides me with a satisfaction that is unlike any others and strengthens my desire to aid their conservation.”

Each chapter includes a map highlighting the areas mentioned, photographs of several of the birds described and an ecological update, the inauguration of a Conservation Area or recent figures relating to the increase/decrease of a particular species.

… This is a book I have particularly enjoyed reading and one I can wholeheartedly recommend to others who enjoy tales of birds, people and unknown localities. Buy now for an engrossing read.

Eunice Spilman, Amazona Society magazine, February 2010.

A definite must-read for parrot lovers, perspective travellers, and those arm chair travellers who would like to escape and travel vicariously through the author’s descriptive accounts of her South American birding adventures…. You can feel Rosemary’s excitement and fascination as she shares some of her most treasured moments of travel. As a parrot lover myself, this book truly fulfilled my craving/desire to read and learn more about parrots. However, this book opened my eyes to admire and value a wider variety of birds. For example, it’s hard not to share the author’s enthusiasm as she recounts the performance of a male Golden-collared Manakin displaying his courtship dance to gain the attention of a potential mate. Or the emotional impact the author felt observing the breathtaking beauty of eight to ten Cock of the Rocks dancing at a lek in Ecuador.

Rosemary was ahead of the times as far as eco tourism birding. A lot has changed in 30 years. She writes: “Today’s birders don’t know how lucky they are!”

This book describes the advances and accomplishments of conservation projects that have helped parrots live longer, better lives in the wild. From land purchases and creating Natural Park reserves to protect habitat and safeguard the parrots; to reintroductions of Scarlet Macaws in Costa Rica by Amigos de los Aves; the reintroduction of Blue and Gold Macaws by Bernadette Plair in Trinidad…

This book was enlightening and fun! Like I was reading my own diary notes of trips I have taken with my husband Mark. Many to the same locations, so I can honestly say this highly regarded author of more than 20 books conveyed an accurate description of the places and projects she visited.

Marie Stafford, Parrots International on-line magazine: 1, 2010.

For those of you who think that Rosemary Low only writes books about parrots -- think again. Although weighted towards parrots, Rosemary’s latest book -- Go West for Parrots! -- is a fascinating insight into Rosemary’s travels over the past 30 years and the vast array of species and people that she has encountered. It is as much a travel log as it is a bird book and as such will be equally treasured by the traveller as it will be by the naturalist.

With its stunning cover shot of Hyacinth Macaws flying over the Pantanal to its charming hand-drawn maps, this book is one which you will find difficult to put down. Rosemary has surpassed herself with the simple but highly effective layout of the book; each chapter covers a particular South American country or island group, and each country has an insert panel within the chapter, with details of interesting and sometimes little known facts about the area. Each chapter concludes with a list of species mentioned in the text, together with their scientific names. .. Each chapter is neatly rounded off with an update, providing details of the latest conservation measures being taken in the area, the current status of the birds, if it has changed, and, even in some cases, updates of the characters she met.

The book is illustrated with numerous photographs which really bring the book to life; these vary from images of the swamp men in Trinidad to Bolivian market scenes and the tranquillity of the Argentinian lakes; and, of course, a wealth of images of birds and other animals. If I had one criticism it would be that all the photographs are in black and white.

In typical Rosemary style, this book is packed with well-written descriptions of wildlife, habitat and the amazing and often humbling characters that she has encountered in her travels. Whether you read it from cover to cover or just dip in to find out more about your next holiday destination, you will not be disappointed. This book deserves a much wider audience than just the avicultural and natural history market. When you buy a copy, why not buy a second copy and give it to a friend who knows nothing about birds. I guarantee that they will enjoy it and, if it does not awake a dormant naturalist and conservationist in them, I will be truly surprised.

David Woolcock (Curator, Paradise Park, Cornwall), Avicultural Magazine.

Translated from the German by Tony Pittman

A spectacular volume with impressive photos of the wild does not await the reader, but a type of travel diary with all the highs and lows, which travellers in remote regions generally experience. The illustrations are monochrome and the maps are drawn by hand. In contrast to other travellers, who are only interested in parrots and parakeets and often wilfully ignore the country and its people, Rosemary Low is enthusiastic about hummingbirds, manakins, raptors and other rare birds and describes comprehensively the not always straight-forward working conditions of local conservationists and the life of the local people… She condemns the destructive greed of oil companies, which in Ecuador seek to destroy the ‘crown jewels’ of the Amazon, praises the successful activities of conservationists in Costa Rica and Argentina, and censures the habitat destruction rolling over Central America.

It is gripping to see how things have changed in the time she has been involved (the author describes 23 journeys taken between 1975 and 2008). This situation was decisive for the author to write this very readable book. Low wishes to alert the reader to the problems of neo-tropical parrots before it is too late.

Rainer Niemann, Papageien, April 2010.

Go West for Parrots ! Comments from readers

Carlos Keller, Brazil

I’m nearly finishing your book and it’s fantastic! I think it’s one of your best books. You’re really a good writer. I was very glad to read about your visit at my farm and I was wondering how are you able to memorize everything in a so detailed way. I never saw you taking notes, but without a journal made every day it would be impossible. Now I’m waiting for the next volume, something like: Go East for Parakeets!

Olivier Chassot, Costa Rica

We would also like to thank you very much for sending us your new book. It was great to be able to share your adventures since the mid seventies, and imagine all the wild places and amazing parrot species that you have had the chance to admire! It was also very exciting to read about some of our colleagues and friends, and of course, we enjoyed a lot your chapter on the Great Green Macaw in Costa Rica. I read the book for Christmas, almost without stopping and really liked it. This was a wonderful gift from you. Thank you again.

Bernadette Plair, Trinidad and USA.

What a delightful and informative narrative of your travels and experiences over the years with parrots and other species in the New World. You are truly an amazing writer.

I was totally surprised to see the chapters you wrote on Trinidad and Tobago. What an amazing tribute to the work done by the people there. Thank you for documenting your experiences with the locals and sharing the true spirit of community based conservation. I am humbled that you attributed so much to me because I could not have done any of it without their help and support. I feel honoured to be represented in your book and to be called a friend by someone with your vast knowledge and outstanding integrity.

READ A CHAPTER

FROM

GO WEST FOR PARROTS!

FROM

GO WEST FOR PARROTS!

Chapter 3. Colombia 1976: Island in the Amazon

My first experience of a tropical rainforest was in Colombia. I was transported into a different world and felt as though I wanted to stay there forever. I had an amazing sense of belonging.

We had left the Andean region on a -hour flight. There were awe-inspiring views, horizon to horizon, of forest canopy, and then the mighty Amazon, a wide ribbon of blue or brown snaking through the verdant forests. Just as the Andes is the world’s longest mountain chain, the Amazon is the river with the greatest volume, pouring forth one fifth of all the river water on earth. Everything seems to be measured in superlatives here. The Amazon basin is immense, covering an area of two and a half million square miles (6.5 million sq km) in nine countries.

We landed in Leticia facing an invisible wall of hot, humid air as the cabin doors opened. Located in the very south of the republic, it is only two and a half miles (4km) from the town of Benjamin Constant in Brazil and the same distance from the Peruvian border. A finger of land reaches down to give Colombia the tiniest frontage on the north bank of the Amazon. On arrival at the hotel, the Parador Ticuna, the new guests were offered an iced whisky and ginger while the process of form-filling was completed.

Stepping outside we encountered various flycatchers, feasting on mosquitoes, and small finches, Black and White Seedeaters, feeding among reeds and grasses. I exclaimed in delight at the sight of a pair of Scarlet-crowned Barbets. Medium-sized and often brightly-coloured, barbets are found throughout the tropics – and this was my very first sighting. The male is striking with the red area stretching over the crown and nape, orange breast and yellow-olive abdomen. The female has the crown and nape frosty white and her colours are more muted. Barbets have prominent bristles above the thick, strong bill with which they excavate nesting sites. The initial observation of a member of a well-known tropical bird family is always an exciting moment for the inexperienced observer. What might soon become commonplace is at this moment awesome.

We walked down to the waterfront. This was the hub of the town where its 20,000 inhabitants# (the population has since doubled) bought and sold fish, fruit and vegetables. It was pulsating with life – with an unseen darker side of which we were innocently unaware but which contributed to the town’s booming economy. Narcotic drugs were bought and sold with as little ceremony as rice and beans. Several cartel leaders grew rich there and built big houses. To move the drugs more easily they constructed eight miles (12 km) of a new highway to the town of Tarapacá before they were arrested and locked up. Their palatial homes were seized by the government.

In Leticia the river was paramount, with floating houses, and a floating petrol station. At the pier we embarked on the picturesque Amazon Queen, a small covered cruise boat, for an evening trip. For 50 minutes before the sun went down we chugged along, wide-eyed at the wonders of the huge river. Dusk fell and myriad bats were flying their rapid, zigzag flight, just above the water. As the sun streaked the clouds with gold and orange, and painted fiery reflections in the water, four macaws flew high, high overhead. My happiness was complete. What a setting for my very first macaws! We returned in complete darkness, the boat chugging through reeds so dense we almost lost faith in our crew. The last patch of colour in the sky had faded behind us.

Behind the hotel stood a large tree – the roosting site of Yellow-rumped Caciques. Every evening these handsome, glossy-black birds came streaming in, 50 or more together. I counted 800 birds! They were handsome with wing patch and under tail coverts of bright yellow, blue eyes and a whitish pointed bill. The noise and activity as they settled down for the night was remarkable! After the caciques came hundreds of White-winged Parakeets, stopping briefly in a large fig tree on their way to the town square.

Next morning we dressed by torchlight at 5am; our accommodation could not boast the sophistication of electricity at that dark hour! We walked purposefully through the streets to the town square. As we approached, two squawking clouds of parakeets flew in starling-like flocks towards the trees on the riverbank. We were just in time to see them depart their roost. The din they created was indescribable! Little 9in (22cm) green birds with longish pointed tails, the white wing patches flashed as they flew in tight, co-ordinated flocks.

Until Colombia ceased its legal bird export trade in 1973, thousands of these unfortunate little parakeets were trapped every year, especially in this area. Trappers would locate the roosting site in the dense cane thickets that line the banks of the Amazon, then cut lanes through the thickets. Here they would erect their mist nets. When the survivors of these trapping activities arrived in Europe and the USA there was little demand, they were sold for about £3 each and soon became unwanted when their harsh voices made them unpopular. It was, like so much of the trade in wild-caught parrots, based not on demand but on making money. Colombia had been one of the world’s major exporters of live birds and animals, also crocodile skins. It was one of the first countries in South America to take an enlightened view and to end the legal trade. (The illegal trade flourishes almost everywhere.)

Late that afternoon three of us left the other members of the group. Dusk fell soon after the canoe pushed off. In the darkness, the three-hour ride to Santa Sofia (also known as Monkey Island), seemed endless. It became colder and colder and rain began to fall. We huddled together, listening to the nocturnal sounds, the unseen insects and the tree frogs. The night shift was very vocal. “What is that noise?” we asked, like all new visitors to a tropical forest. The main vocalists are the cicadas, winged insects not unlike grasshoppers. How could anything so small make so much noise, we wondered? But there must have been millions of them out there, drowning out the chorus of frogs and the cries of hunting owls.

The boatman’s headlamp permeated the darkness for floating logs and other dangers. At last we arrived at the wooden lodge, a palm-thatched building on stilts, on the riverbank, to be served dinner by the light of paraffin lamps. In this idyllic spot, 240 miles (384km) south of the Equator, dusk fell and dawn broke at 5.30am.

This, my first ever experience of the rainforest, was paradise! To be in an environment not dominated by man is, in itself, a potentially life-changing experience for anyone from the concrete jungle of the so-called civilised world. After a couple of days England was forgotten, as remote as the moon.

My first experience of a tropical rainforest was in Colombia. I was transported into a different world and felt as though I wanted to stay there forever. I had an amazing sense of belonging.

We had left the Andean region on a -hour flight. There were awe-inspiring views, horizon to horizon, of forest canopy, and then the mighty Amazon, a wide ribbon of blue or brown snaking through the verdant forests. Just as the Andes is the world’s longest mountain chain, the Amazon is the river with the greatest volume, pouring forth one fifth of all the river water on earth. Everything seems to be measured in superlatives here. The Amazon basin is immense, covering an area of two and a half million square miles (6.5 million sq km) in nine countries.

We landed in Leticia facing an invisible wall of hot, humid air as the cabin doors opened. Located in the very south of the republic, it is only two and a half miles (4km) from the town of Benjamin Constant in Brazil and the same distance from the Peruvian border. A finger of land reaches down to give Colombia the tiniest frontage on the north bank of the Amazon. On arrival at the hotel, the Parador Ticuna, the new guests were offered an iced whisky and ginger while the process of form-filling was completed.

Stepping outside we encountered various flycatchers, feasting on mosquitoes, and small finches, Black and White Seedeaters, feeding among reeds and grasses. I exclaimed in delight at the sight of a pair of Scarlet-crowned Barbets. Medium-sized and often brightly-coloured, barbets are found throughout the tropics – and this was my very first sighting. The male is striking with the red area stretching over the crown and nape, orange breast and yellow-olive abdomen. The female has the crown and nape frosty white and her colours are more muted. Barbets have prominent bristles above the thick, strong bill with which they excavate nesting sites. The initial observation of a member of a well-known tropical bird family is always an exciting moment for the inexperienced observer. What might soon become commonplace is at this moment awesome.

We walked down to the waterfront. This was the hub of the town where its 20,000 inhabitants# (the population has since doubled) bought and sold fish, fruit and vegetables. It was pulsating with life – with an unseen darker side of which we were innocently unaware but which contributed to the town’s booming economy. Narcotic drugs were bought and sold with as little ceremony as rice and beans. Several cartel leaders grew rich there and built big houses. To move the drugs more easily they constructed eight miles (12 km) of a new highway to the town of Tarapacá before they were arrested and locked up. Their palatial homes were seized by the government.

In Leticia the river was paramount, with floating houses, and a floating petrol station. At the pier we embarked on the picturesque Amazon Queen, a small covered cruise boat, for an evening trip. For 50 minutes before the sun went down we chugged along, wide-eyed at the wonders of the huge river. Dusk fell and myriad bats were flying their rapid, zigzag flight, just above the water. As the sun streaked the clouds with gold and orange, and painted fiery reflections in the water, four macaws flew high, high overhead. My happiness was complete. What a setting for my very first macaws! We returned in complete darkness, the boat chugging through reeds so dense we almost lost faith in our crew. The last patch of colour in the sky had faded behind us.

Behind the hotel stood a large tree – the roosting site of Yellow-rumped Caciques. Every evening these handsome, glossy-black birds came streaming in, 50 or more together. I counted 800 birds! They were handsome with wing patch and under tail coverts of bright yellow, blue eyes and a whitish pointed bill. The noise and activity as they settled down for the night was remarkable! After the caciques came hundreds of White-winged Parakeets, stopping briefly in a large fig tree on their way to the town square.

Next morning we dressed by torchlight at 5am; our accommodation could not boast the sophistication of electricity at that dark hour! We walked purposefully through the streets to the town square. As we approached, two squawking clouds of parakeets flew in starling-like flocks towards the trees on the riverbank. We were just in time to see them depart their roost. The din they created was indescribable! Little 9in (22cm) green birds with longish pointed tails, the white wing patches flashed as they flew in tight, co-ordinated flocks.

Until Colombia ceased its legal bird export trade in 1973, thousands of these unfortunate little parakeets were trapped every year, especially in this area. Trappers would locate the roosting site in the dense cane thickets that line the banks of the Amazon, then cut lanes through the thickets. Here they would erect their mist nets. When the survivors of these trapping activities arrived in Europe and the USA there was little demand, they were sold for about £3 each and soon became unwanted when their harsh voices made them unpopular. It was, like so much of the trade in wild-caught parrots, based not on demand but on making money. Colombia had been one of the world’s major exporters of live birds and animals, also crocodile skins. It was one of the first countries in South America to take an enlightened view and to end the legal trade. (The illegal trade flourishes almost everywhere.)

Late that afternoon three of us left the other members of the group. Dusk fell soon after the canoe pushed off. In the darkness, the three-hour ride to Santa Sofia (also known as Monkey Island), seemed endless. It became colder and colder and rain began to fall. We huddled together, listening to the nocturnal sounds, the unseen insects and the tree frogs. The night shift was very vocal. “What is that noise?” we asked, like all new visitors to a tropical forest. The main vocalists are the cicadas, winged insects not unlike grasshoppers. How could anything so small make so much noise, we wondered? But there must have been millions of them out there, drowning out the chorus of frogs and the cries of hunting owls.

The boatman’s headlamp permeated the darkness for floating logs and other dangers. At last we arrived at the wooden lodge, a palm-thatched building on stilts, on the riverbank, to be served dinner by the light of paraffin lamps. In this idyllic spot, 240 miles (384km) south of the Equator, dusk fell and dawn broke at 5.30am.

This, my first ever experience of the rainforest, was paradise! To be in an environment not dominated by man is, in itself, a potentially life-changing experience for anyone from the concrete jungle of the so-called civilised world. After a couple of days England was forgotten, as remote as the moon.

The Lodge on Monkey Island

Until man’s impact, little had changed in the rainforest in 100 million years. Such a period of time is incomprehensible. In comparison, the temperate forests of Europe and North America are only 11,000 years old. Tropical forests occupy approximately only 6% of the earth’s surface but they are believed to harbour about 50% of its biodiversity, that is, the plant and animal life. The neotropics contain approximately 57% of all remaining rainforest.

Tropical forests differ fundamentally from temperate ones in harbouring a huge number of species of birds and trees but with relatively few individuals of each. The nearer you go to the Equator, the greater the diversity. Except for the myriad insects, including brightly coloured stink bugs and huge black rhinoceros beetles (so called for the impressive curved horns), you have to look carefully to find living creatures. Most of the birds and animals live high, high above but there is plenty to see from ground level. The newcomer to the Amazon rainforest needs to be quite still every now and then and examine the small details among the forest giants: the finely etched variegated leaves of a Peperomia vine (more familiar as a house plant!) climbing up a trunk and the brown moth camouflaged against its bark. The huge buttressed roots can trip you up if your eyes are pointed skywards following the line of the trunk which might lack branches until it reaches the canopy. Tangles of lianas, like green velvet-covered ropes, make patterns between the trees and create highways for smaller creatures. We soon ceased to comment on the orchids growing on trees, no rarer than marsh marigolds beside an English river.

These forests tend to be quiet for long periods. Then suddenly the silence is broken by a troop of monkeys rampaging through the trees and stillness becomes frenzied activity when a dozen or more species of small birds arrive calling and chattering to follow an ant swarm. The ants disturb small creatures that run for cover in the wake of the tiny predators. This is the moment that birders are waiting for. They become as frenetic as the feeding birds in trying to spot and identify antbirds, anthrushes and other species over the space of a couple of minutes. Then the forest reverts to a state of tranquillity.

Santa Sofia Island had been bought by animal dealer Mike Tsilickis in 1967. There were reputed to be 25,000 squirrel monkeys there. Originally 6,000 were released, the aim being that the offspring would supply the dreadful trade in primates used for research. However, they had not been trapped for three years due to export restrictions on all native species.

There are no seasons relating to temperature on Monkey Island: only wet and dry. This was the time during which nearly all land was under water. The flood can extend for 25 miles or more on each side of the riverbed so bird watching took place from a motorised canoe. There was plenty to see. David, a young American who had been working at the lodge for 18 months, had identified 164 species.

With our boatmen Baptisto and Haroldo, we would cross the great expanse of the Amazon and enter a tributary, cutting the engine and drifting. In places the river looked like a meadow, tightly covered by a dense growth of tiny aquatic plants. Our boatmen struggled with one oar to get us through. Sometimes branches hung so low we had to flatten ourselves in the bottom of the canoe and might be showered with termites from the overhanging vegetation. But we were too excited by this wonderful new world to be discouraged by a few bites!

A common species seen among the reeds in small groups was the Yellow-headed Blackbird or Marshbird. The striking male is glossy black with head and upper breast bright golden yellow, while the female is brown and dull yellow. Another inhabitant of the reeds was the Black-capped Mockingthrush whose loud, monotonous song was often heard.

More spectacular inhabitants of the tributaries were the birds known locally as kamungo. My first glimpse, of a pair flying across the river in front of the canoe, gave the momentary impression of a huge eagle. Its plumage was mainly black with a green sheen, except for the white abdomen. Then the realisation dawned that they were Horned Screamers, apparently related to geese. The “horn” is a forward-curving spike on the forehead, which may reach 6in (15cm) in length. The powerful legs of these birds are bare of feathers so that they can wade through flooded forest. Their long toes support them when they walk on floating vegetation. They alone of living birds share with the primitive Archaeopteryx the distinction of lacking the small bony straps that strengthen the rib cage. The boatmen seemed bemused at our interest in what was, to them, a good meal. They told us that the water hyacinth is one of the screamer’s principal foods. These birds often flew high, spiralling gradually upwards. Their honking and braying calls, said to carry for two miles, were among the most characteristic sounds of the area.

We had not been going for long when Baptista whispered “Cigano!” -- and pointed. All we could see was a dark shape perched among the branches. He eased the canoe forward and we had a perfect view. As we came closer, the bird displayed in threat, with rounded chestnut wings opening and closing and tail spread to reveal the white patches on the end of the tail. Then to the left we saw a pair. They were Hoatzins. My first sighting of one of the world’s strangest and most primitive birds produced a great feeling of elation. The red eyes set in the tiny head are surrounded by bare blue skin and the tall spiky buff-brown feathers of the crest give them a slightly rakish look.

They flap clumsily around in vegetation, flying little, and usually only to the nearest tree. They are said to feed entirely on leaves but in Haroldo’s view the diet consisted only of new shoots. Their digestion is so poor that these stay in the stomach for two days. Bacteria in the greatly enlarged oesophagus and crop aid digestion. This process is similar to stomach fermentation in cows.

The Hoatzin’s best known peculiarity is the unique behaviour off its chicks. On hatching and until the age of three weeks they have two well developed, functional claws at the tip of each wing – another link to the Archaeopteryx. This intriguing fact has led to the speculation that the Hoatzin might be a link in the evolution of birds from reptiles. It all sounds like a tall story but the chicks can swim and if they fall into the water below, either accidentally or perhaps evading a predator; the claws enable them to clamber along branches back to the platform of sticks that form the nest!

Watching Hoatzins gave me a strange sensation that I never felt before or since, as though the clock had been turned back tens of thousands of years when these ancient birds perhaps lived among dinosaurs.

Palm trees with a multitude of long, vicious spines grow along the waterlogged riverbanks, interspersed with a thick tangle of riverine undergrowth. As we rounded a bend I saw a cluster of conures feeding in a smooth-trunked palm close to the water’s edge. I called to Haroldo to stop. He edged the canoe right under the palm and I could recognise Black-tailed Conures, so engrossed that they seemed oblivious to our presence. Also called Maroon-tailed Parakeets, they are green with breast feathers scalloped in greyish-white and rosy-red wing coverts. White-winged Parakeets were feeding with them on the fruits of a Euterpe palm. There were about 35 parakeets in all, some sitting in small groups mutual-preening, others clinging to the trunk of the palm where they had gnawed away two large areas of bark, too low down to be protected by the overhanging fronds. We watched them for several minutes until a small parrot flew over at great speed and, with much shrieking, the whole flock took to the air in alarm.

We often saw flocks of parakeets – usually Aratinga species such as the Dusky-headed and the White-eyed. The most common small parrot was the Short-tailed which resembles a miniature Amazon. We soon learned to recognise their double call note. Blue-headed Pionus and Mealy Amazons were often seen, also the most common Amazon, found only in riverine habitat, the Festive. Late one afternoon, as dusk was falling, a flock of about 25 flew across the river towards the island, heading for their roost. I was intrigued to see one detach itself from the flock and return to the mainland. Perhaps it had just remembered its mate!

It was rewarding to explore the tiny creeks. Sometimes we had to duck or lie low as we negotiated the hazardous branches hanging over the river. Baptisto and Haroldo laughed with us. They invariably saw birds before we did, so attuned were they to this watery environment. Boating in a flooded forest is an experience to be recalled again and again – a unique adventure in a fascinating landscape where fish swim among trees. The scenery has an indescribable beauty, especially when lit by the sun. The tall, gnarled, white-barked trees made an incongruous contrast to the lushness elsewhere. They were not dead. When the waters receded they would come back to life as the oxygen once again penetrated their roots. Occasionally we would encounter a native family, crammed into a tiny canoe with a dog. They were paddling so close to the water-line, you wondered how they kept afloat.

On the first afternoon we identified 30 bird species; this would be a derisory total for real birders! As dusk fell and the bats came out from their roost, a nightjar with white-banded wings darted past.

Early morning was the best time for birds. Canoeing slowly through the creeks and searching the trees, we were rewarded with a handsome Crimson-crested Woodpecker, colourful araçaris (small toucans) and a Slaty-tailed Trogon sitting quietly, waiting to pounce on a moth. Trogons, typical and widespread birds of the tropics, are colourful and elegant, with metallic shining blue-green upperparts and, in this species, carmine underparts, set off by a long, broad tail. Suddenly encountering a Black-necked Red Cotinga was enthralling. A study in crimson and black, he had a short silky crimson crest, crimson body and tail, and velvety black mantle and neck. A flock of fifteen Blue and Yellow Macaws were leaving their roosting site and the calls of raucous Festive Amazons rang out through the forest.

At the lodge there was a resident Festive, completely reliable in temperament, who could be handled by anyone. This parrot species is an exceptional mimic. “Aurora” could spell out his name, laugh and repeat many words in Spanish. He was full-winged and spent most of his time in the trees outside the lodge or visiting the kitchen for tit-bits. It was a sobering thought that Aurora would almost certainly have ended up in the pot had someone not befriended him. The local people have no sentiment about the fauna they encounter. At the lodge we saw a snake (not a common event, as these reptiles avoid man) and were pleased to photograph it. Unfortunately, our activity brought it to the attention of two small boys who speared it and drowned it as soon as we walked away.

One day the lunch fare was not so good; apparently the cook was short of food. When the usual afternoon rains ceased at 3.30pm we canoed over to some floating homes with David to enquire after fish or eggs. There were none. Eventually David procured a chicken. It was tied by the legs and put in the canoe. I got out of the way while the cook killed and prepared the unfortunate chicken. It was very tough – but David ate his. The unspecified meat with which we were served on another occasion was, almost certainly, monkey. Most humans consider that a meal is incomplete without animal protein. While I can survive anywhere on beans and rice that view would not be popular with most diners.

One morning when the rain was pouring down, I was up at first light hoping it would cease. No one else had stirred. I sat in the dry, at the lodge door, and filmed the creatures that appeared before me: a gallinule, a kite, a snake and the friendly Black-fronted Nunbirds, dark with the bill red. My favourite was an antpitta, species unidentified, who rushed around, flinging aside leaves, in his search for insects. Antpittas are long-legged, short-tailed birds, the equivalent of the colourful Asiatic pittas but garbed more soberly in shades of brown.

The rain finally ceased and we ventured out in the canoe to visit an Indian village. It was called Arara after the large number of macaws in the area. Here lived Ticuna Indians, organised and artistic people who, even after 400

Tropical forests differ fundamentally from temperate ones in harbouring a huge number of species of birds and trees but with relatively few individuals of each. The nearer you go to the Equator, the greater the diversity. Except for the myriad insects, including brightly coloured stink bugs and huge black rhinoceros beetles (so called for the impressive curved horns), you have to look carefully to find living creatures. Most of the birds and animals live high, high above but there is plenty to see from ground level. The newcomer to the Amazon rainforest needs to be quite still every now and then and examine the small details among the forest giants: the finely etched variegated leaves of a Peperomia vine (more familiar as a house plant!) climbing up a trunk and the brown moth camouflaged against its bark. The huge buttressed roots can trip you up if your eyes are pointed skywards following the line of the trunk which might lack branches until it reaches the canopy. Tangles of lianas, like green velvet-covered ropes, make patterns between the trees and create highways for smaller creatures. We soon ceased to comment on the orchids growing on trees, no rarer than marsh marigolds beside an English river.

These forests tend to be quiet for long periods. Then suddenly the silence is broken by a troop of monkeys rampaging through the trees and stillness becomes frenzied activity when a dozen or more species of small birds arrive calling and chattering to follow an ant swarm. The ants disturb small creatures that run for cover in the wake of the tiny predators. This is the moment that birders are waiting for. They become as frenetic as the feeding birds in trying to spot and identify antbirds, anthrushes and other species over the space of a couple of minutes. Then the forest reverts to a state of tranquillity.

Santa Sofia Island had been bought by animal dealer Mike Tsilickis in 1967. There were reputed to be 25,000 squirrel monkeys there. Originally 6,000 were released, the aim being that the offspring would supply the dreadful trade in primates used for research. However, they had not been trapped for three years due to export restrictions on all native species.

There are no seasons relating to temperature on Monkey Island: only wet and dry. This was the time during which nearly all land was under water. The flood can extend for 25 miles or more on each side of the riverbed so bird watching took place from a motorised canoe. There was plenty to see. David, a young American who had been working at the lodge for 18 months, had identified 164 species.

With our boatmen Baptisto and Haroldo, we would cross the great expanse of the Amazon and enter a tributary, cutting the engine and drifting. In places the river looked like a meadow, tightly covered by a dense growth of tiny aquatic plants. Our boatmen struggled with one oar to get us through. Sometimes branches hung so low we had to flatten ourselves in the bottom of the canoe and might be showered with termites from the overhanging vegetation. But we were too excited by this wonderful new world to be discouraged by a few bites!

A common species seen among the reeds in small groups was the Yellow-headed Blackbird or Marshbird. The striking male is glossy black with head and upper breast bright golden yellow, while the female is brown and dull yellow. Another inhabitant of the reeds was the Black-capped Mockingthrush whose loud, monotonous song was often heard.

More spectacular inhabitants of the tributaries were the birds known locally as kamungo. My first glimpse, of a pair flying across the river in front of the canoe, gave the momentary impression of a huge eagle. Its plumage was mainly black with a green sheen, except for the white abdomen. Then the realisation dawned that they were Horned Screamers, apparently related to geese. The “horn” is a forward-curving spike on the forehead, which may reach 6in (15cm) in length. The powerful legs of these birds are bare of feathers so that they can wade through flooded forest. Their long toes support them when they walk on floating vegetation. They alone of living birds share with the primitive Archaeopteryx the distinction of lacking the small bony straps that strengthen the rib cage. The boatmen seemed bemused at our interest in what was, to them, a good meal. They told us that the water hyacinth is one of the screamer’s principal foods. These birds often flew high, spiralling gradually upwards. Their honking and braying calls, said to carry for two miles, were among the most characteristic sounds of the area.

We had not been going for long when Baptista whispered “Cigano!” -- and pointed. All we could see was a dark shape perched among the branches. He eased the canoe forward and we had a perfect view. As we came closer, the bird displayed in threat, with rounded chestnut wings opening and closing and tail spread to reveal the white patches on the end of the tail. Then to the left we saw a pair. They were Hoatzins. My first sighting of one of the world’s strangest and most primitive birds produced a great feeling of elation. The red eyes set in the tiny head are surrounded by bare blue skin and the tall spiky buff-brown feathers of the crest give them a slightly rakish look.

They flap clumsily around in vegetation, flying little, and usually only to the nearest tree. They are said to feed entirely on leaves but in Haroldo’s view the diet consisted only of new shoots. Their digestion is so poor that these stay in the stomach for two days. Bacteria in the greatly enlarged oesophagus and crop aid digestion. This process is similar to stomach fermentation in cows.

The Hoatzin’s best known peculiarity is the unique behaviour off its chicks. On hatching and until the age of three weeks they have two well developed, functional claws at the tip of each wing – another link to the Archaeopteryx. This intriguing fact has led to the speculation that the Hoatzin might be a link in the evolution of birds from reptiles. It all sounds like a tall story but the chicks can swim and if they fall into the water below, either accidentally or perhaps evading a predator; the claws enable them to clamber along branches back to the platform of sticks that form the nest!

Watching Hoatzins gave me a strange sensation that I never felt before or since, as though the clock had been turned back tens of thousands of years when these ancient birds perhaps lived among dinosaurs.

Palm trees with a multitude of long, vicious spines grow along the waterlogged riverbanks, interspersed with a thick tangle of riverine undergrowth. As we rounded a bend I saw a cluster of conures feeding in a smooth-trunked palm close to the water’s edge. I called to Haroldo to stop. He edged the canoe right under the palm and I could recognise Black-tailed Conures, so engrossed that they seemed oblivious to our presence. Also called Maroon-tailed Parakeets, they are green with breast feathers scalloped in greyish-white and rosy-red wing coverts. White-winged Parakeets were feeding with them on the fruits of a Euterpe palm. There were about 35 parakeets in all, some sitting in small groups mutual-preening, others clinging to the trunk of the palm where they had gnawed away two large areas of bark, too low down to be protected by the overhanging fronds. We watched them for several minutes until a small parrot flew over at great speed and, with much shrieking, the whole flock took to the air in alarm.

We often saw flocks of parakeets – usually Aratinga species such as the Dusky-headed and the White-eyed. The most common small parrot was the Short-tailed which resembles a miniature Amazon. We soon learned to recognise their double call note. Blue-headed Pionus and Mealy Amazons were often seen, also the most common Amazon, found only in riverine habitat, the Festive. Late one afternoon, as dusk was falling, a flock of about 25 flew across the river towards the island, heading for their roost. I was intrigued to see one detach itself from the flock and return to the mainland. Perhaps it had just remembered its mate!

It was rewarding to explore the tiny creeks. Sometimes we had to duck or lie low as we negotiated the hazardous branches hanging over the river. Baptisto and Haroldo laughed with us. They invariably saw birds before we did, so attuned were they to this watery environment. Boating in a flooded forest is an experience to be recalled again and again – a unique adventure in a fascinating landscape where fish swim among trees. The scenery has an indescribable beauty, especially when lit by the sun. The tall, gnarled, white-barked trees made an incongruous contrast to the lushness elsewhere. They were not dead. When the waters receded they would come back to life as the oxygen once again penetrated their roots. Occasionally we would encounter a native family, crammed into a tiny canoe with a dog. They were paddling so close to the water-line, you wondered how they kept afloat.

On the first afternoon we identified 30 bird species; this would be a derisory total for real birders! As dusk fell and the bats came out from their roost, a nightjar with white-banded wings darted past.

Early morning was the best time for birds. Canoeing slowly through the creeks and searching the trees, we were rewarded with a handsome Crimson-crested Woodpecker, colourful araçaris (small toucans) and a Slaty-tailed Trogon sitting quietly, waiting to pounce on a moth. Trogons, typical and widespread birds of the tropics, are colourful and elegant, with metallic shining blue-green upperparts and, in this species, carmine underparts, set off by a long, broad tail. Suddenly encountering a Black-necked Red Cotinga was enthralling. A study in crimson and black, he had a short silky crimson crest, crimson body and tail, and velvety black mantle and neck. A flock of fifteen Blue and Yellow Macaws were leaving their roosting site and the calls of raucous Festive Amazons rang out through the forest.

At the lodge there was a resident Festive, completely reliable in temperament, who could be handled by anyone. This parrot species is an exceptional mimic. “Aurora” could spell out his name, laugh and repeat many words in Spanish. He was full-winged and spent most of his time in the trees outside the lodge or visiting the kitchen for tit-bits. It was a sobering thought that Aurora would almost certainly have ended up in the pot had someone not befriended him. The local people have no sentiment about the fauna they encounter. At the lodge we saw a snake (not a common event, as these reptiles avoid man) and were pleased to photograph it. Unfortunately, our activity brought it to the attention of two small boys who speared it and drowned it as soon as we walked away.

One day the lunch fare was not so good; apparently the cook was short of food. When the usual afternoon rains ceased at 3.30pm we canoed over to some floating homes with David to enquire after fish or eggs. There were none. Eventually David procured a chicken. It was tied by the legs and put in the canoe. I got out of the way while the cook killed and prepared the unfortunate chicken. It was very tough – but David ate his. The unspecified meat with which we were served on another occasion was, almost certainly, monkey. Most humans consider that a meal is incomplete without animal protein. While I can survive anywhere on beans and rice that view would not be popular with most diners.

One morning when the rain was pouring down, I was up at first light hoping it would cease. No one else had stirred. I sat in the dry, at the lodge door, and filmed the creatures that appeared before me: a gallinule, a kite, a snake and the friendly Black-fronted Nunbirds, dark with the bill red. My favourite was an antpitta, species unidentified, who rushed around, flinging aside leaves, in his search for insects. Antpittas are long-legged, short-tailed birds, the equivalent of the colourful Asiatic pittas but garbed more soberly in shades of brown.

The rain finally ceased and we ventured out in the canoe to visit an Indian village. It was called Arara after the large number of macaws in the area. Here lived Ticuna Indians, organised and artistic people who, even after 400

The Flooded Forest

The rain finally ceased and we ventured out in the canoe to visit an Indian village. It was called Arara after the large number of macaws in the area. Here lived Ticuna Indians, organised and artistic people who, even after 400 years of contact with white men, have preserved their identity through their language, religion and cultural art forms. They do, however, wear Western-style clothes. These river people rarely go far inland. They are skilled boat builders. In this village they grew most of their own food, plus rice as a cash crop. With the money they bought an engine for their communal boat and ran their own ferry service. To take a man to Leticia the charge was 10 pesos (61 pesos to the pound, at that time) for a man, two pesos for a woman and one peso for a child.

The village was situated in a clearing and the areas around the dwellings were clean and tidy. In one building their artwork was displayed for sale. It was apparent that they were talented basket makers, sculptors and mask makers. Using bark cloth they produced beautiful paintings and masks and dolls, all in their distinctive style. The soft whitish cloth has the appearance of paper and, for under £2, I bought a painting of birds and snakes made from this cloth and decorated using vegetable dyes. Animals were favourite themes; tanagers and owls were recognisable in the paintings and jaguars and alligators were the subjects of exquisitely produced funeral masks. These masks are worn during the funeral dance and represent the creatures that the deceased will hunt in the next life.

I learned that these hard-working people refused to be registered as Colombian citizens until they were provided with electricity and a school, which the children attend from the age of seven. Many aspects of their lives were quite sophisticated yet, I was told, girls have their hair pulled out at puberty and must wear a headscarf until it grows. Then they are married.

These industrious people contrasted in a striking manner with the Yagua tribe who we had visited on a previous occasion, after an hour’s journey downriver by speedboat. Their village consisted of four open-sided abodes with only a thatched roof and a raised floor. Their appearance was more primitive. The men, with hair cropped short, wore skirts made of palm strips dyed orange with plant juice. They were pleased to demonstrate their prowess with blowpipes as long as they were tall. Skilful hunters, they use the poison that tips their arrows in a number of different strengths according to the size of the prey and whether it is to be killed or stunned.

The women were dressed in red cotton material wrapped around the waist. The children wore nothing or a cotton wrap. In one dwelling a baby and a small child swung in hammocks while a woman casually peeled some fruit while swinging in hers. Just by being there I felt as though I was intruding. An old man accepted the packet of cigarettes the tour leader brought as a gift. One might envy their simple life yet the women were old beyond their years: they carried young babies but their faces were lined and without the lustre of youth. The Yaguas seldom live in groups of more than about 30 people. Once this number is exceeded, a new village is formed. Unlike most tribes, their numbers were increasing, we were told.

When the canoe came to take us away from the lodge on the island I was sad. Living so close to nature, with the great Amazon river just 2ft (60cm) beneath my bed, I had forgotten everything about the developed world. Here nothing was important but one’s surroundings. But back in Leticia running water (on the island, bucket showers were the order of the day), a toilet that flushed and fish for supper with fried potatoes, all seemed like the height of luxury. And here was a Fasciated Antshrike, who boasted no bright colours but was exquisitely barred and spotted in black and white. The female is chestnut and cinnamon. I was to meet this species or a closely allied one on other occasions, in different countries in the neotropics, and I always relished those encounters with these perky birds that have so much personality.

The village was situated in a clearing and the areas around the dwellings were clean and tidy. In one building their artwork was displayed for sale. It was apparent that they were talented basket makers, sculptors and mask makers. Using bark cloth they produced beautiful paintings and masks and dolls, all in their distinctive style. The soft whitish cloth has the appearance of paper and, for under £2, I bought a painting of birds and snakes made from this cloth and decorated using vegetable dyes. Animals were favourite themes; tanagers and owls were recognisable in the paintings and jaguars and alligators were the subjects of exquisitely produced funeral masks. These masks are worn during the funeral dance and represent the creatures that the deceased will hunt in the next life.

I learned that these hard-working people refused to be registered as Colombian citizens until they were provided with electricity and a school, which the children attend from the age of seven. Many aspects of their lives were quite sophisticated yet, I was told, girls have their hair pulled out at puberty and must wear a headscarf until it grows. Then they are married.

These industrious people contrasted in a striking manner with the Yagua tribe who we had visited on a previous occasion, after an hour’s journey downriver by speedboat. Their village consisted of four open-sided abodes with only a thatched roof and a raised floor. Their appearance was more primitive. The men, with hair cropped short, wore skirts made of palm strips dyed orange with plant juice. They were pleased to demonstrate their prowess with blowpipes as long as they were tall. Skilful hunters, they use the poison that tips their arrows in a number of different strengths according to the size of the prey and whether it is to be killed or stunned.

The women were dressed in red cotton material wrapped around the waist. The children wore nothing or a cotton wrap. In one dwelling a baby and a small child swung in hammocks while a woman casually peeled some fruit while swinging in hers. Just by being there I felt as though I was intruding. An old man accepted the packet of cigarettes the tour leader brought as a gift. One might envy their simple life yet the women were old beyond their years: they carried young babies but their faces were lined and without the lustre of youth. The Yaguas seldom live in groups of more than about 30 people. Once this number is exceeded, a new village is formed. Unlike most tribes, their numbers were increasing, we were told.

When the canoe came to take us away from the lodge on the island I was sad. Living so close to nature, with the great Amazon river just 2ft (60cm) beneath my bed, I had forgotten everything about the developed world. Here nothing was important but one’s surroundings. But back in Leticia running water (on the island, bucket showers were the order of the day), a toilet that flushed and fish for supper with fried potatoes, all seemed like the height of luxury. And here was a Fasciated Antshrike, who boasted no bright colours but was exquisitely barred and spotted in black and white. The female is chestnut and cinnamon. I was to meet this species or a closely allied one on other occasions, in different countries in the neotropics, and I always relished those encounters with these perky birds that have so much personality.

You would think that any writer would relish recounting a dramatic, life-threatening incident -- or might even invent one to make the story more exciting. I did not need to invent one and I do not enjoy reliving it. Avianca flight 70 departed from Bogota on our return journey. Scheduled as a jumbo jet it was replaced with a Boeing 727 which, I later discovered, had already left the airport once that day but returned unfit to fly. The flight was delayed while mechanics repaired it for a flight across the Atlantic. As the engines revved-up for take-off, three hours late, I watched huge flames leaping from one engine. The aircraft lumbered into the sky but its obvious lack of power, jolting and shuddering progress, and failure of the air conditioning resulted in some anxiety (to say the least) among the passengers. Half an hour later once again the sight of flames shooting from one engine did nothing to reassure me of a happy landing. This engine, too, was shut off, with evident further loss of power. Most of the passengers were of Latin origin and panic and prayers to God were spreading through the aircraft.

Miraculously, a safe unscheduled landing was made at Barranquilla where the flight was delayed more than two hours while a new set of mechanics attempted to rectify the trouble. It was with no little apprehension that the passengers re-embarked. The engines were revved up for take-off and the aircraft taxied on to the runway. The take-off was aborted and the captain radioed to the control tower in a message that was live all over the aircraft. He was unable to take off due to “technical difficulties”. It was 11.45pm. In order to avoid the expense of hotel accommodation for 200 people, delaying tactics were taken by the airline and it was announced that a meal would be served.

Due to the malfunction of almost everything on the plane, the food was inedible and the heat in the cabin became stifling. Tension among the passengers was mounting. Most people on board feared another take-off on an obviously faulty aircraft. What was the airline playing at? Our group intended to find out. Our leader Mrs Salt, a travel agent of 25 years’ standing, asked a stewardess to bring the chief steward. She was told to sit down. That was too much! We did not take kindly to being addressed like naughty children.

I accompanied her to the captain’s cabin (on reflection, it is amazing that we were not forbidden entry) where Mrs Salt told the captain she was appalled at the conditions under which passengers on the flight were being carried. I could not resist adding that I was a Fleet Street journalist (I omitted the word magazine!) and that Avianca could be getting some very bad publicity (assuming we lived to tell the tale). Evidently the captain had no wish for a further confrontation with two determined and irate British females and immediately the announcement Cancelado was made. Passengers were directed to leave the aircraft.

That was not the end of the ordeal. An unfortunate Avianca clerk then had to secure hotels for 200 people. Allocation for our group was (perhaps not unsurprisingly) left to last and it was well past 2am when we trundled tiredly to our accommodation. Without doubt it was the worst I have ever seen. The beds were so filthy we did not dare to sleep in them, the air conditioning unit was broken and the room was running with cockroaches and other insects. The captain’s payback, perhaps? We finally reached London 23 hours late.

Apart from this incident, I was most impressed by the courteousness and kindness of all the people with whom I came into contact. It is regrettable that because the country’s reputation is founded more on drug barons than on scenic delights and exceptional diversity of bird life, it is not better known to visitors.

Miraculously, a safe unscheduled landing was made at Barranquilla where the flight was delayed more than two hours while a new set of mechanics attempted to rectify the trouble. It was with no little apprehension that the passengers re-embarked. The engines were revved up for take-off and the aircraft taxied on to the runway. The take-off was aborted and the captain radioed to the control tower in a message that was live all over the aircraft. He was unable to take off due to “technical difficulties”. It was 11.45pm. In order to avoid the expense of hotel accommodation for 200 people, delaying tactics were taken by the airline and it was announced that a meal would be served.

Due to the malfunction of almost everything on the plane, the food was inedible and the heat in the cabin became stifling. Tension among the passengers was mounting. Most people on board feared another take-off on an obviously faulty aircraft. What was the airline playing at? Our group intended to find out. Our leader Mrs Salt, a travel agent of 25 years’ standing, asked a stewardess to bring the chief steward. She was told to sit down. That was too much! We did not take kindly to being addressed like naughty children.

I accompanied her to the captain’s cabin (on reflection, it is amazing that we were not forbidden entry) where Mrs Salt told the captain she was appalled at the conditions under which passengers on the flight were being carried. I could not resist adding that I was a Fleet Street journalist (I omitted the word magazine!) and that Avianca could be getting some very bad publicity (assuming we lived to tell the tale). Evidently the captain had no wish for a further confrontation with two determined and irate British females and immediately the announcement Cancelado was made. Passengers were directed to leave the aircraft.

That was not the end of the ordeal. An unfortunate Avianca clerk then had to secure hotels for 200 people. Allocation for our group was (perhaps not unsurprisingly) left to last and it was well past 2am when we trundled tiredly to our accommodation. Without doubt it was the worst I have ever seen. The beds were so filthy we did not dare to sleep in them, the air conditioning unit was broken and the room was running with cockroaches and other insects. The captain’s payback, perhaps? We finally reached London 23 hours late.

Apart from this incident, I was most impressed by the courteousness and kindness of all the people with whom I came into contact. It is regrettable that because the country’s reputation is founded more on drug barons than on scenic delights and exceptional diversity of bird life, it is not better known to visitors.

2008 update

The Colombian government announced its plans to expand biofuel production with the opening of twenty plants within the next decade. A planned 7.4 million acres of “unused farmlands” would be converted to plantations of African oil palms. In fact they planned to use primary forests on the colonization frontier of the Chocó and Amazon regions. This will be a tragedy for the biodiversity of the regions and for many endangered bird species. The misguided demand for biofuels is accelerating deforestation throughout the tropics.

All photographs and text on this website are the copyright of |