LOOKING BACK: LORO PARQUE

Looking Back: Loro Parque

1987 - 1989

1987 - 1989

I have often been asked what it was like to be curator of the world’s largest parrot collection. As in any bird collection, it brought joy and despair and frustration -- but in this case total immersion in the job, lots of sunshine (the Canary Islands can boast one of the best and healthiest climates in the world) and a very different way of life. Loro Parque was also my home as I lived in the grounds with my then partner, Mike Gammond, who went on to care for a large bird collection in Bahrain.

During the late 1980s, when I was curator, Tenerife’s foremost tourist attraction was a very different place to that which visitors see today. It was more intimate, and with much greater emphasis on the parrots. The first of the huge popular exhibits, the dolphin pool and arena, was opened.

Loro Parque stood out like a sea of exotic vegetation among the banana plantations in the small coastal community of Punta Brava. Only the main road and the beach separated the park from the ocean. It was (and still is) a beautiful location, almost part of the village. The flora of the park is especially rich and varied; it is also a beautifully maintained botanical garden, with a cactus area (with lizards darting out to feed on the dropped flowers), countless palm trees, a huge strangler fig in a small forest of trees, a large bed of orange lilies (where the Pionus aviaries now stand) and many flowering shrubs such as bougainvillea and oleander (poisonous to parrots). The big flamingo lawn, bordered with flamboyant orange bird of paradise flowers was like the focal point. Nearby the free-flying macaws put on a show several times a day, flying through hoops (and sometimes ending up in a palm tree!). It was never the same when the show was moved inside.

For me, the park lost some of its immediate charm when it expanded into the huge tourist attraction that it is today. I remember fondly the small entrance, on the main street, over which a wooden image of a Leadbeater’s Cockatoo modestly displayed the words “Loro Parque”. How different to the impressively wide steps leading up to today’s gilded temple entrance presided over by a huge, magnificent bronze of a cockatoo!

Our first few weeks there were difficult as we knew no Spanish and relied on the always obliging biologist, Aranxta, to interpret.

Fortunately, this situation did not last long. In fact, I think the key to our success there was the very good relationship we had with the bird keepers, who numbered seven or eight at that time. We all got on well together: it was almost like being part of a large family.

Today there are many hundreds of employees.

During the late 1980s, when I was curator, Tenerife’s foremost tourist attraction was a very different place to that which visitors see today. It was more intimate, and with much greater emphasis on the parrots. The first of the huge popular exhibits, the dolphin pool and arena, was opened.

Loro Parque stood out like a sea of exotic vegetation among the banana plantations in the small coastal community of Punta Brava. Only the main road and the beach separated the park from the ocean. It was (and still is) a beautiful location, almost part of the village. The flora of the park is especially rich and varied; it is also a beautifully maintained botanical garden, with a cactus area (with lizards darting out to feed on the dropped flowers), countless palm trees, a huge strangler fig in a small forest of trees, a large bed of orange lilies (where the Pionus aviaries now stand) and many flowering shrubs such as bougainvillea and oleander (poisonous to parrots). The big flamingo lawn, bordered with flamboyant orange bird of paradise flowers was like the focal point. Nearby the free-flying macaws put on a show several times a day, flying through hoops (and sometimes ending up in a palm tree!). It was never the same when the show was moved inside.

For me, the park lost some of its immediate charm when it expanded into the huge tourist attraction that it is today. I remember fondly the small entrance, on the main street, over which a wooden image of a Leadbeater’s Cockatoo modestly displayed the words “Loro Parque”. How different to the impressively wide steps leading up to today’s gilded temple entrance presided over by a huge, magnificent bronze of a cockatoo!

Our first few weeks there were difficult as we knew no Spanish and relied on the always obliging biologist, Aranxta, to interpret.

Fortunately, this situation did not last long. In fact, I think the key to our success there was the very good relationship we had with the bird keepers, who numbered seven or eight at that time. We all got on well together: it was almost like being part of a large family.

Today there are many hundreds of employees.

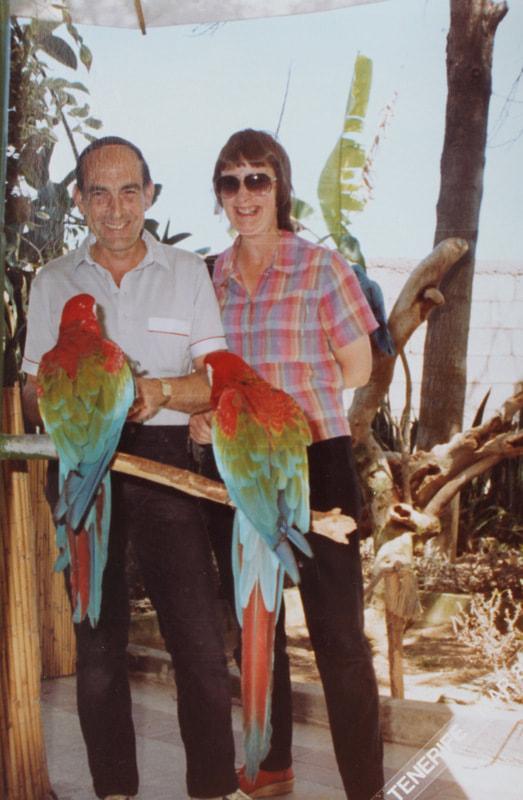

Rosemary and Mike: Loro Parque 1987

At that time the parrot collection numbered about 1,300 individuals. Not all were on exhibit. There was a large well-designed breeding centre behind the chimpanzee exhibit (the chimps having been rescued from photographers). We set up a second off-exhibit breeding centre where most of the pairs (not species such as cockatoos that like to walk around on the ground) were kept in suspended cages. These are suitable in the warm and often cloudy climate of north Tenerife (not as hot as the south of the island). The main disadvantage of this wonderful climate, the lack of rain, was overcome by fitting all aviaries with sprinklers.

By the time we left in 1989, this breeding centre contained 160 suspended cages, some of them very large and high for macaws. We set up about 20 young pairs because it was just being discovered that the larger macaws were becoming endangered due to excessive trade and loss of habitat. I could see that the day was coming when these birds would (rightly) no longer be available from the wild. At that time the collection held all the macaws currently known in captivity, except Lear’s (then represented by only three birds outside Brazil) and the blue-headed (Ara couloni) which was on the brink of being introduced to aviculture.

My favourite aviaries on exhibit were the four -- the only ones in the park -- which housed more than one pair of birds. A large, high aviary measuring about 40ft x 20ft (12m x 6m), housed a group of Moluccan Cockatoos (of course, wild-caught in those days). Watching the behaviour of the flock of fifteen was absolutely fascinating. On occasions, these highly intelligent birds would assemble on the ground in a group of six to eight, and stand together as though in discussion.

As with any species, colony breeding brought problems. There was an egg thief, who would remove an egg from a nest (how he climbed with it to the top of the nest without breaking it was a mystery -- and if it had been thrown out it would have broken), take it to a high perch and turn it round and round in his foot until disturbed. Then it would drop to the ground and smash.

Another favourite enclosure of mine was that for the colony of Budgerigars. It was always a pleasure to watch the constant activity. The public, too, loved this aviary. Nearby was the aviary for Pesquet’s Parrots (the breeding pair was off-exhibit). I will never cease to be amazed by this unique black and scarlet species.

In total contrast, where rarity was concerned, was the enclosure at the end of the row of lory aviaries that contained five Orange-breasted Fig Parrots. These gorgeous little birds were available for only a very short time, in limited numbers, and have never been established in captivity.

Diminutive parrots, 5in (13cm) in length, they were among the most fascinating I have ever had in my care. They reminded me of miniature Black-headed Caiques, having a similar shape and stance, and black and orange in the plumage. Endlessly active, they were a joy to observe, especially on the days when all the parrots in the park were given fresh branches of pine or casuarina. These were soon reduced to a pile of wood chippings. Captive fig parrots tended to suffer from overgrown beaks (also like caiques) so fresh branches for gnawing were essential.

By the time we left in 1989, this breeding centre contained 160 suspended cages, some of them very large and high for macaws. We set up about 20 young pairs because it was just being discovered that the larger macaws were becoming endangered due to excessive trade and loss of habitat. I could see that the day was coming when these birds would (rightly) no longer be available from the wild. At that time the collection held all the macaws currently known in captivity, except Lear’s (then represented by only three birds outside Brazil) and the blue-headed (Ara couloni) which was on the brink of being introduced to aviculture.

My favourite aviaries on exhibit were the four -- the only ones in the park -- which housed more than one pair of birds. A large, high aviary measuring about 40ft x 20ft (12m x 6m), housed a group of Moluccan Cockatoos (of course, wild-caught in those days). Watching the behaviour of the flock of fifteen was absolutely fascinating. On occasions, these highly intelligent birds would assemble on the ground in a group of six to eight, and stand together as though in discussion.

As with any species, colony breeding brought problems. There was an egg thief, who would remove an egg from a nest (how he climbed with it to the top of the nest without breaking it was a mystery -- and if it had been thrown out it would have broken), take it to a high perch and turn it round and round in his foot until disturbed. Then it would drop to the ground and smash.

Another favourite enclosure of mine was that for the colony of Budgerigars. It was always a pleasure to watch the constant activity. The public, too, loved this aviary. Nearby was the aviary for Pesquet’s Parrots (the breeding pair was off-exhibit). I will never cease to be amazed by this unique black and scarlet species.

In total contrast, where rarity was concerned, was the enclosure at the end of the row of lory aviaries that contained five Orange-breasted Fig Parrots. These gorgeous little birds were available for only a very short time, in limited numbers, and have never been established in captivity.

Diminutive parrots, 5in (13cm) in length, they were among the most fascinating I have ever had in my care. They reminded me of miniature Black-headed Caiques, having a similar shape and stance, and black and orange in the plumage. Endlessly active, they were a joy to observe, especially on the days when all the parrots in the park were given fresh branches of pine or casuarina. These were soon reduced to a pile of wood chippings. Captive fig parrots tended to suffer from overgrown beaks (also like caiques) so fresh branches for gnawing were essential.

Orange-breasted Fig Parrot at Loro Parque 1988

The other aviary I could never pass without stopping to observe the occupants was that for the Greater Vasa Parrots. Being entirely dark grey, vasas are the least colourful parrots in existence. They are also, behaviourally, the most bizarre -- next to the Kakapo. At that time I described them as “the most endearing and interesting of all parrots”! Their love of sunbathing and the strange positions they assume when engaged in this activity, and their unique breeding biology, easily compensated for their lack of colour and unusual appearance.

Quite a few parrot species flew free in the park -- some of which had arrived from an unknown location, possibly the open window of a disillusioned owner. My favourite free flyers were undoubtedly the Dusky Lories. We bred an excess of males so a number of them were released. They were the most fearless and attractive free-flyers imaginable. I have always maintained that lories have a sense of humour and this little gang delighted in terrorising groups of visitors by hurtling between them at eye level. (Lories on the wing are very fast!)

Quite a few parrot species flew free in the park -- some of which had arrived from an unknown location, possibly the open window of a disillusioned owner. My favourite free flyers were undoubtedly the Dusky Lories. We bred an excess of males so a number of them were released. They were the most fearless and attractive free-flyers imaginable. I have always maintained that lories have a sense of humour and this little gang delighted in terrorising groups of visitors by hurtling between them at eye level. (Lories on the wing are very fast!)

Dusky Lory at liberty in the park.

Our home was a large apartment in the park above the office. Out on the elevated spacious terrace (with its wonderful view of distant Mount Teide) we kept our own birds, mainly Amazons and lories. We were visited by some of the free-flying Quaker Parakeets in the park. One pair had a nest in a palm tree about 10ft (3m) above our terrace. From our patio I could watch the dramas there unfold. The nest in the next palm tree was less readily observed but its occupants were instantly recognisable by their beak deformities. “Longbeak”, who I think was the female, had an immensely overgrown upper mandible whereas her partner, “Beaky”, totally lacked an upper mandible. He appreciated the moistened bread that I put out on the terrace but obviously had survived without any problem before we arrived.

The Quakers would start to nest in March, laying five or six eggs. The first young would leave the nest at the end of May. One day, it was May 30, to be precise, there was a tremendous commotion at the nest overhanging the terrace. Mitred Conures were at liberty in the park. Although the Quakers outnumbered them by hundreds to one, the Quakers seemed afraid of them. When the conures decided to investigate a big stick nest, they did not fight back. They evicted the last chick from the nest. It sat forlornly below the untidy bundle of twigs that had been its home for the past seven weeks, uninjured but not yet able to fly. We gave it to a friend who hand-reared it. This was the first of several similar occurrences -- but the people of Tenerife love parrots and there was never a shortage of volunteers to take ejected young.

The Quakers would start to nest in March, laying five or six eggs. The first young would leave the nest at the end of May. One day, it was May 30, to be precise, there was a tremendous commotion at the nest overhanging the terrace. Mitred Conures were at liberty in the park. Although the Quakers outnumbered them by hundreds to one, the Quakers seemed afraid of them. When the conures decided to investigate a big stick nest, they did not fight back. They evicted the last chick from the nest. It sat forlornly below the untidy bundle of twigs that had been its home for the past seven weeks, uninjured but not yet able to fly. We gave it to a friend who hand-reared it. This was the first of several similar occurrences -- but the people of Tenerife love parrots and there was never a shortage of volunteers to take ejected young.

Rosemary in the hand-rearing room with a

Triton Cockatoo and a Moluccan Cockatoo.

Triton Cockatoo and a Moluccan Cockatoo.

At weekends I worked in the hand-rearing room which was just a small space next to the garage which held the park’s vehicles. What a contrast to today’s wonderful “Baby Station”. The room had a window through which visitors could watch the ever-fascinating sight of chicks being spoon-fed. Yes, I allowed syringes to be used only for large macaws and cockatoos!

In the evening, when all the visitors had departed, we could watch the Crowned Cranes dancing on the lawn in front of the flamingo pond. However, when you live above “the shop” there is not much time for relaxation! But this was an extraordinary experience which taught me so much and which I look back on with some nostalgia.

I think my main fault as a curator was being too emotionally involved with the birds! That is something which will never be ironed out of me.

In the evening, when all the visitors had departed, we could watch the Crowned Cranes dancing on the lawn in front of the flamingo pond. However, when you live above “the shop” there is not much time for relaxation! But this was an extraordinary experience which taught me so much and which I look back on with some nostalgia.

I think my main fault as a curator was being too emotionally involved with the birds! That is something which will never be ironed out of me.

All photographs and text on this website are the copyright of |