KAKAPO

Kakapo Conservation and Don Merton

By Rosemary Low

By Rosemary Low

New Zealand is an exceptionally beautiful country with some of the most spectacular scenery found anywhere in the world. You can see plenty of birds there but sadly most of them are European species brought out by 19th century settlers. A 2007 survey which gained 2,000 responses, showed that Blackbirds occur in 90% of gardens, House Sparrows in 83% and Starlings in 54% of “backyards”. Native birds are seldom seen in gardens.

More than one quarter of all New Zealand’s birds are extinct. Fifty-eight of these extinctions have occurred since the arrival of the human race. Numbers of all New Zealand’s parrots have declined catastrophically – some to the edge of extinction. The reasons are twofold – loss of habitat and the introduction of predatory mammals.

None has suffered more than the Kakapo (Strigops habroptilus) – probably the most unique bird to have existed in historical times due to its extraordinary breeding biology and physical attributes. It is perhaps also the most charismatic, even the most endearing. The world's heaviest parrot, males weigh up to 3.7kg and females up to 2kg. It is flightless (the only flightless parrot). It has a facial disc of sensory bristle-like feathers from which arose the now obsolete name of Owl Parrot. When walking, its body and head are held horizontally.

It is also one of the most critically endangered birds on earth. Because it is nocturnal and flightless, the Kakapo was almost wiped out by introduced predators such as cats, stoats and rats. These trusting parrots were killed in their thousands two or three centuries ago, for skins, for food and even to feed dogs. In the early 1980s, the threat from mammalian predators was the reason for the removal of the few surviving birds to offshore island reserves that had been cleared of predators by the Department of Conservation. Kakapo are officially declared extinct in the wild, although, of course, they live at complete freedom on the island reserves.

More than one quarter of all New Zealand’s birds are extinct. Fifty-eight of these extinctions have occurred since the arrival of the human race. Numbers of all New Zealand’s parrots have declined catastrophically – some to the edge of extinction. The reasons are twofold – loss of habitat and the introduction of predatory mammals.

None has suffered more than the Kakapo (Strigops habroptilus) – probably the most unique bird to have existed in historical times due to its extraordinary breeding biology and physical attributes. It is perhaps also the most charismatic, even the most endearing. The world's heaviest parrot, males weigh up to 3.7kg and females up to 2kg. It is flightless (the only flightless parrot). It has a facial disc of sensory bristle-like feathers from which arose the now obsolete name of Owl Parrot. When walking, its body and head are held horizontally.

It is also one of the most critically endangered birds on earth. Because it is nocturnal and flightless, the Kakapo was almost wiped out by introduced predators such as cats, stoats and rats. These trusting parrots were killed in their thousands two or three centuries ago, for skins, for food and even to feed dogs. In the early 1980s, the threat from mammalian predators was the reason for the removal of the few surviving birds to offshore island reserves that had been cleared of predators by the Department of Conservation. Kakapo are officially declared extinct in the wild, although, of course, they live at complete freedom on the island reserves.

One of the hundreds of mounted Kakapo around the world at Te Anau Visitors’ Centre in New Zeala

Photographs © Rosemary Low

Photographs © Rosemary Low

Codfish (Maori name Whenua Hou) is a small island just off the south coast of South Island. Nearly 4km of turbulent ocean separates it from Stewart Island to the east. It was on Stewart that the last wild population of Kakapo was discovered in 1977. Before that, the species was believed to be effectively extinct, as only m ales were known to survive. Females were especially vulnerable to predation as they tended their nests on the ground. Kakapo breed approximately every three years, being stimulated by the fruiting of the rimu shrub.

Males have a traditional display ground. They are alone among parrots in having an inflatable thoracic air sac, used to make a booming call to attract females from a wide distance. After a male mates with a female, she goes off alone to lay eggs and rear the young. When chicks hatch, the females walk miles every night in search of food – shoots and berries.

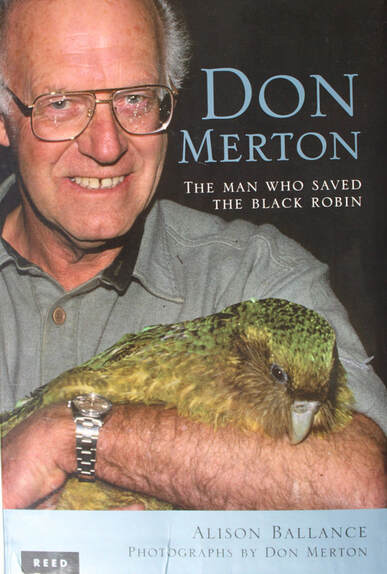

Synonymous with the story of the Kakapo’s last-minute reprieve from extinction is the name of Don Merton. His involvement with Kakapo commenced in 1958, as a trainee with the Wildlife Service. He was part of the team that searched for this species on the mainland when it was almost extinct there. Until the day he retired in 2005, his contribution to the Kakapo Recovery Programme (especially as leader) was enormous. His understanding of this parrot and its biology, his intuition and his determination were major factors that prevented its extinction. His career was remarkable and recognised worldwide and in New Zealand with awards such as the Queen’s Service Medal 1989 (conservation of endangered species) and “one of One Hundred Great New Zealander’s of the 20th Century” (1999). His impact on bird preservation was far-reaching.

For years I had dreamed of seeing a Kakapo. My dream came true in September 1993 at a time when only 47 Kakapo were known to survive. I spent unforgettable days in the company of Don and his wife Margaret. Don was quiet and unassuming, warm and friendly, with an engaging smile and a mind which seemed to solve any practical problem connected with bird conservation. I never met anyone who was more single-minded, determined and dedicated in achieving his goal, inspiring everyone he met.

We flew down to Nelson in the South Island then we drove to Havelock, a little fishing town. There we boarded a motor boat for the one-hour journey to Maud Island. As we approached I saw a rugged, bush-covered land, rising quite steeply out of the ocean. In 1977 farming ceased and the sheep were removed. The island, which covers 309 hectares, was bought by the Wildlife Service and cleared of predatory mammals. The bush regenerated with amazing rapidity; secondary growth then covered almost the entire island.

In 1993 there were six Kakapo on Maud Island, a Department of Conservation reserve to which outsiders are not normally admitted. The Kakapo included "Hoki", the young one who was hand-reared in 1992, having been taken from Codfish Island as a starving chick of five and a half weeks. The chick’s plight was not due to parental neglect but caused by a lack of suitable rearing foods.

On that first afternoon, we climbed up high. It was a sunny day in early spring and the sky was blue. Don pointed out unmistakable signs of Kakapo. These include "chews" -- fibrous plant material, especially grasses, ejected as compressed pellets. Either they are still attached to the plant, hanging in little balls, or they are found on the ground. I saw Kakapo droppings along their tracks, usually as distinctive oblong piles. I picked up a soft, newly-moulted Kakapo feather. Now all I wanted was to see a Kakapo!

Eagerly I awaited nightfall, which was cold. Four of us went out to look for Hoki. We sat quietly and she came to see us, nibbling our shoes and climbing up on Gideon, who she knew so well. Next night Don and I went out again. We had the unforgettable experience of watching Hoki by moonlight. We sat quietly for an hour and were rewarded with seeing her behave as Kakapo have done for millennia, moving about, often on the run, feeding on grasses. That memory has never left me. To see a parrot as big and round and cuddly as a large cat, and nearly as close to extinction as the Dodo, moving around more like a mammal than a bird, was surreal. This was heightened by the moonlit night. To have a Kakapo actually standing on one’s foot is a privilege afforded to very, very few. For me, it was the experience of a lifetime!

Don took a number of photos of me with Hoki -- pictures that should have been treasured mementos. Alas, they were lost en route from the developers!

Males have a traditional display ground. They are alone among parrots in having an inflatable thoracic air sac, used to make a booming call to attract females from a wide distance. After a male mates with a female, she goes off alone to lay eggs and rear the young. When chicks hatch, the females walk miles every night in search of food – shoots and berries.

Synonymous with the story of the Kakapo’s last-minute reprieve from extinction is the name of Don Merton. His involvement with Kakapo commenced in 1958, as a trainee with the Wildlife Service. He was part of the team that searched for this species on the mainland when it was almost extinct there. Until the day he retired in 2005, his contribution to the Kakapo Recovery Programme (especially as leader) was enormous. His understanding of this parrot and its biology, his intuition and his determination were major factors that prevented its extinction. His career was remarkable and recognised worldwide and in New Zealand with awards such as the Queen’s Service Medal 1989 (conservation of endangered species) and “one of One Hundred Great New Zealander’s of the 20th Century” (1999). His impact on bird preservation was far-reaching.

For years I had dreamed of seeing a Kakapo. My dream came true in September 1993 at a time when only 47 Kakapo were known to survive. I spent unforgettable days in the company of Don and his wife Margaret. Don was quiet and unassuming, warm and friendly, with an engaging smile and a mind which seemed to solve any practical problem connected with bird conservation. I never met anyone who was more single-minded, determined and dedicated in achieving his goal, inspiring everyone he met.

We flew down to Nelson in the South Island then we drove to Havelock, a little fishing town. There we boarded a motor boat for the one-hour journey to Maud Island. As we approached I saw a rugged, bush-covered land, rising quite steeply out of the ocean. In 1977 farming ceased and the sheep were removed. The island, which covers 309 hectares, was bought by the Wildlife Service and cleared of predatory mammals. The bush regenerated with amazing rapidity; secondary growth then covered almost the entire island.

In 1993 there were six Kakapo on Maud Island, a Department of Conservation reserve to which outsiders are not normally admitted. The Kakapo included "Hoki", the young one who was hand-reared in 1992, having been taken from Codfish Island as a starving chick of five and a half weeks. The chick’s plight was not due to parental neglect but caused by a lack of suitable rearing foods.

On that first afternoon, we climbed up high. It was a sunny day in early spring and the sky was blue. Don pointed out unmistakable signs of Kakapo. These include "chews" -- fibrous plant material, especially grasses, ejected as compressed pellets. Either they are still attached to the plant, hanging in little balls, or they are found on the ground. I saw Kakapo droppings along their tracks, usually as distinctive oblong piles. I picked up a soft, newly-moulted Kakapo feather. Now all I wanted was to see a Kakapo!

Eagerly I awaited nightfall, which was cold. Four of us went out to look for Hoki. We sat quietly and she came to see us, nibbling our shoes and climbing up on Gideon, who she knew so well. Next night Don and I went out again. We had the unforgettable experience of watching Hoki by moonlight. We sat quietly for an hour and were rewarded with seeing her behave as Kakapo have done for millennia, moving about, often on the run, feeding on grasses. That memory has never left me. To see a parrot as big and round and cuddly as a large cat, and nearly as close to extinction as the Dodo, moving around more like a mammal than a bird, was surreal. This was heightened by the moonlit night. To have a Kakapo actually standing on one’s foot is a privilege afforded to very, very few. For me, it was the experience of a lifetime!

Don took a number of photos of me with Hoki -- pictures that should have been treasured mementos. Alas, they were lost en route from the developers!

Hoki in 1993

Gideon Climo with Hoki. Photographs © Rosemary Low

It was also a privilege to be with Don, whose boyhood dream, from the age of 12, had been to save the endangered birds of his country. By the time I first met him, he had spent 40 years doing that. He has perhaps made a greater contribution to saving endangered birds (not only in New Zealand) than any man alive. He told me: “My work is to attempt to avert extinction and facilitate recovery of endangered life forms. Where man is responsible, either directly or indirectly, for causing their demise, he has a moral obligation to at least attempt a remedy.”

In April 1999 I was able to renew my acquaintance with the extraordinary Kakapo. This was the first year ever in which females in this intensively managed population laid for the third successive year. Normally there are two or more years between egg-laying according to the masting (fruiting) of food trees. The circumstances were unique. The rat eradication programme on Codfish Island in 1998 necessitated all 26 Kakapo there being relocated, some to Pearl Island. In December at least nine out of the ten males there started to boom -- a prelude to breeding activity. By the end of February at least five more females had laid. There was a danger of egg and chick predation, so eggs were removed to an incubator.

Meanwhile, an extraordinary event was taking place on Little Barrier Island. A female Kakapo named Lisa, not seen for 13 years, was sitting on three fertile eggs! Her eggs were removed to the incubator on South Island at the DOC rearing unit. In April I was privileged to spend two days there. Seven chicks had hatched, varying in age from 17 to 42 days. I was elated that within the space of a month the population of the Kakapo had increased from 56 to 63. No one was “counting their chickens” and, sadly, one chick died, but the hatchings represented significant progress in so many respects that there was good reason for elation.

In April 1999 I was able to renew my acquaintance with the extraordinary Kakapo. This was the first year ever in which females in this intensively managed population laid for the third successive year. Normally there are two or more years between egg-laying according to the masting (fruiting) of food trees. The circumstances were unique. The rat eradication programme on Codfish Island in 1998 necessitated all 26 Kakapo there being relocated, some to Pearl Island. In December at least nine out of the ten males there started to boom -- a prelude to breeding activity. By the end of February at least five more females had laid. There was a danger of egg and chick predation, so eggs were removed to an incubator.

Meanwhile, an extraordinary event was taking place on Little Barrier Island. A female Kakapo named Lisa, not seen for 13 years, was sitting on three fertile eggs! Her eggs were removed to the incubator on South Island at the DOC rearing unit. In April I was privileged to spend two days there. Seven chicks had hatched, varying in age from 17 to 42 days. I was elated that within the space of a month the population of the Kakapo had increased from 56 to 63. No one was “counting their chickens” and, sadly, one chick died, but the hatchings represented significant progress in so many respects that there was good reason for elation.

Kakapo chicks being hand-reared in 1999. Photographs © Rosemary Low

My first sight of a Kakapo chick, a 42-day-old male, was one which I will always remember. Fully feathered, he slept peacefully in an air-conditioned room. With other parrot chicks maintaining a high enough temperature is important. With Kakapo, once feathered, the priority is keeping them cool. This is because the female, as a single parent, must leave the chicks for long periods at night to obtain food. With a thick down and the ability to become torpid, they are adapted for survival in low temperatures.

When I saw Lisa’s three chicks I experienced a sense of wonder. Kakapo chicks are rarely seen by humans – and here were much-needed females! In a plastic box, sleeping with heads and feet entwined, was the boost which the Kakapo conservation programme needed so desperately. I gazed for a long time at the young ones, with their enormous feet, prominent ear openings and green feathers just emerging.

This century started with only 62 Kakapo in existence, every one monitored. Then in 2002 occurred the most productive breeding season since intensive management began (in 1989). It went on to become a year of quite extraordinary success with twenty-four chicks reared! They included 15 much-needed females. By the first week in February 19 of the 21 females had either mated or laid. A team of volunteers watched the nests every night to ensure the chicks came to no harm while the female was out foraging and heat pads were used to ensure the eggs did not chill.

Kakapo nested again in 2005, adding another four young to the population. For the first time ever, members of the public had the opportunity to see Kakapo on June 18 2005. The four young were put on display in a glass enclosure before being moved from the rearing unit in Nelson to Codfish Island. Several thousand people queued in the rain to see them.

In 2006 the paying public had the opportunity to see a hand-reared male Kakapo called “Sirocco”. Uniquely, he proved to be too imprinted for breeding purposes. DOC decided to display him for several weeks on Ulva Island. Taking a boat trip to the island, thirty people were able to view him in a night. These included three visitors who had flown in from the USA especially for the purpose.

In 2008, eight chicks were hatched. One died shortly afterwards due to septicaemia. Probably due to a shortage of food, females were spending long periods off the nest so the other seven eggs were artificially incubated. All hatched and six were reared, three males and three females. This brought the total Kakapo population to 91 – 44 females and 47 males. During the second weekend in June, five thousand people queued at the Brook Waimarama Sanctuary in Nelson, South Island to see the six young Kakapo hand-reared that year. With their soft olive-green and yellowish plumage, innocent little faces and almost teddy-bearish appeal, they charmed everyone who saw them. Their next stop was Invercargill for another public viewing, then they were transferred to Codfish Island for eventual release.

One of the females who bred was Hoki, the first young female to survive since 1981. She had been taken from Codfish Island as a starving chick of five and a half weeks. The year was 1993. In September of that year I was accorded a unique privilege. Don Merton took me to Maud Island in Pelorous Sound, where Hoki was living. One moonlight night Don and I had a visit from Hoki. We sat quietly for one hour and were rewarded in seeing her behave as Kakapo have done for millennia, moving about, often on the run, feeding on grasses. I was intrigued by unexpected behaviour traits, such as moving her head from side to side, more like a bird of prey judging distance, than a parrot. In a lifetime of watching parrots and other birds, this is the memory I treasure most.

The 2009 breeding season was the long-awaited most successful breeding season since Kakapo have been under human management. An incredible 29 of the 38 breeding-age females nested; 27 females produced 28 clutches, resulting in 71 eggs! Of these 50 were fertile. This represented about 70% of eggs laid, an increase on the two previous breeding seasons, aided with the use of artificial insemination.

Thirty-six chicks hatched and 33 survived -- 20 males and 13 females. For the first time the human-managed population exceeded one hundred Kakapo! Seven were parent-reared in natural nests and the rest were hand-reared away from Codfish Island where they hatched. The chicks could not have survived without intervention as most of the rimu fruit, on which Kakapo depend for rearing, failed to ripen.

When I saw Lisa’s three chicks I experienced a sense of wonder. Kakapo chicks are rarely seen by humans – and here were much-needed females! In a plastic box, sleeping with heads and feet entwined, was the boost which the Kakapo conservation programme needed so desperately. I gazed for a long time at the young ones, with their enormous feet, prominent ear openings and green feathers just emerging.

This century started with only 62 Kakapo in existence, every one monitored. Then in 2002 occurred the most productive breeding season since intensive management began (in 1989). It went on to become a year of quite extraordinary success with twenty-four chicks reared! They included 15 much-needed females. By the first week in February 19 of the 21 females had either mated or laid. A team of volunteers watched the nests every night to ensure the chicks came to no harm while the female was out foraging and heat pads were used to ensure the eggs did not chill.

Kakapo nested again in 2005, adding another four young to the population. For the first time ever, members of the public had the opportunity to see Kakapo on June 18 2005. The four young were put on display in a glass enclosure before being moved from the rearing unit in Nelson to Codfish Island. Several thousand people queued in the rain to see them.

In 2006 the paying public had the opportunity to see a hand-reared male Kakapo called “Sirocco”. Uniquely, he proved to be too imprinted for breeding purposes. DOC decided to display him for several weeks on Ulva Island. Taking a boat trip to the island, thirty people were able to view him in a night. These included three visitors who had flown in from the USA especially for the purpose.

In 2008, eight chicks were hatched. One died shortly afterwards due to septicaemia. Probably due to a shortage of food, females were spending long periods off the nest so the other seven eggs were artificially incubated. All hatched and six were reared, three males and three females. This brought the total Kakapo population to 91 – 44 females and 47 males. During the second weekend in June, five thousand people queued at the Brook Waimarama Sanctuary in Nelson, South Island to see the six young Kakapo hand-reared that year. With their soft olive-green and yellowish plumage, innocent little faces and almost teddy-bearish appeal, they charmed everyone who saw them. Their next stop was Invercargill for another public viewing, then they were transferred to Codfish Island for eventual release.

One of the females who bred was Hoki, the first young female to survive since 1981. She had been taken from Codfish Island as a starving chick of five and a half weeks. The year was 1993. In September of that year I was accorded a unique privilege. Don Merton took me to Maud Island in Pelorous Sound, where Hoki was living. One moonlight night Don and I had a visit from Hoki. We sat quietly for one hour and were rewarded in seeing her behave as Kakapo have done for millennia, moving about, often on the run, feeding on grasses. I was intrigued by unexpected behaviour traits, such as moving her head from side to side, more like a bird of prey judging distance, than a parrot. In a lifetime of watching parrots and other birds, this is the memory I treasure most.

The 2009 breeding season was the long-awaited most successful breeding season since Kakapo have been under human management. An incredible 29 of the 38 breeding-age females nested; 27 females produced 28 clutches, resulting in 71 eggs! Of these 50 were fertile. This represented about 70% of eggs laid, an increase on the two previous breeding seasons, aided with the use of artificial insemination.

Thirty-six chicks hatched and 33 survived -- 20 males and 13 females. For the first time the human-managed population exceeded one hundred Kakapo! Seven were parent-reared in natural nests and the rest were hand-reared away from Codfish Island where they hatched. The chicks could not have survived without intervention as most of the rimu fruit, on which Kakapo depend for rearing, failed to ripen.

Flossie’s two chicks, a male and a female on April 15 1998. The side of the nest is visible.

Don would reinforce the nest when the female left at night, to protect it from rain and to prevent collapse.

Photograph © Don Merton

Don would reinforce the nest when the female left at night, to protect it from rain and to prevent collapse.

Photograph © Don Merton

Recent breeding seasons

The extraordinary successes in 2008-2009 have not been repeated. There was no breeding in the 2009-2010 season. The following year was good, with eleven young reared. In the season of 2011-2012 no breeding occurred. Sadly, due to the failure of the rimu crop, as a result of one of the coldest springs ever recorded, 2012 to 2013 also failed. Never, since study of the rimu crop commenced in 1997, has there been such a poor rimu fruiting.

In April 2012 seven Kakapo were airlifted to Little Barrier Island, located north of Auckland. The island was home to Kakapo from 1982 to 1999; it was then cleared of rats. The birds now on Little Barrier will be left to breed without intervention. Can they do it? Only time will tell. At the close of 2012, there were 125 Kakapo in existence.

Although numbers have increased, the reproduction rate needs to be much faster and the population more widely dispersed if Kakapo are to survive over the long term.

Island sanctuaries

During the past 20 years, Kakapo have been placed by DOC on eight islands from which all predators had been eradicated. Don Merton told me in May 2008 that he believed they should be more widely dispersed. "This would allow Kakapo to exploit food sources that are possibly more nutritious, more frequent and more reliable than rimu, such as white pine. It would also remove the potentially very serious problem of male Kakapo interfering with the nests of females (this has already happened) due to the Kakapo carrying capacity of an island being exceeded." Disease, fire or some other catastrophe could wipe out the entire adult population.

One of his greatest concerns was that Anchor Island, where the surplus males live, and islands earmarked for future Kakapo releases, are within swimming range of stoats and it will not be possible to keep them free of these bloodthirsty creatures.

The extraordinary successes in 2008-2009 have not been repeated. There was no breeding in the 2009-2010 season. The following year was good, with eleven young reared. In the season of 2011-2012 no breeding occurred. Sadly, due to the failure of the rimu crop, as a result of one of the coldest springs ever recorded, 2012 to 2013 also failed. Never, since study of the rimu crop commenced in 1997, has there been such a poor rimu fruiting.

In April 2012 seven Kakapo were airlifted to Little Barrier Island, located north of Auckland. The island was home to Kakapo from 1982 to 1999; it was then cleared of rats. The birds now on Little Barrier will be left to breed without intervention. Can they do it? Only time will tell. At the close of 2012, there were 125 Kakapo in existence.

Although numbers have increased, the reproduction rate needs to be much faster and the population more widely dispersed if Kakapo are to survive over the long term.

Island sanctuaries

During the past 20 years, Kakapo have been placed by DOC on eight islands from which all predators had been eradicated. Don Merton told me in May 2008 that he believed they should be more widely dispersed. "This would allow Kakapo to exploit food sources that are possibly more nutritious, more frequent and more reliable than rimu, such as white pine. It would also remove the potentially very serious problem of male Kakapo interfering with the nests of females (this has already happened) due to the Kakapo carrying capacity of an island being exceeded." Disease, fire or some other catastrophe could wipe out the entire adult population.

One of his greatest concerns was that Anchor Island, where the surplus males live, and islands earmarked for future Kakapo releases, are within swimming range of stoats and it will not be possible to keep them free of these bloodthirsty creatures.

All photographs and text on this website are the copyright of |